URBAN WILDLIFE: LEARNING TO CO+EXIST

ABOUT THE EXHIBIT

This mixed-media exhibition explores the lives of wild animals in urban areas and the human responses to this shared territory. In preparation for this exhibit, we invited artists to collaborate with scientists who study urban environments and the interactions between urban wildlife and humans. The goal is to encourage the viewing public to take an active role in healthy co-existence with urban wildlife and their habitats.

The expansion of our cities and towns often results in negative human-wildlife conflict. Urban sprawl creates new homes for some animals, even as it displaces others. The results are often problematic.

Science can provide us with guidelines for how to live in balance with urban animals. For example, if we understand coyote behavior – they follow food sources – we can avoid problems. But we need the motivation to apply these solutions to our daily lives. There is an equally important need to help more people understand that humans and animals are interdependent and that our continued success depends on a diverse and healthy animal kingdom. This is a juried exhibit.

See the slideshow below for artwork from our first exhibit on this topic, which premiered in 2018 at the Rhode Island School of Design.

EXHIBIT SLIDESHOW

URBAN WILDLIFE: LEARNING TO CO+EXIST at RISD Summer 2018

Hover on each image for more information

Coyotes are a generalist species. I find their ability to adapt to and expand into environments modified by humans, including urban areas, fascinating. The symbolic and representational images of different species depict features of the coyotes diet taken from data gathered both in urban areas as well as rural spaces to show the diversity of food sources. I collaborated with Joel Ruprecht , who studies coyotes in North Eastern Oregon in the Starkey Experimental Forest. By collecting scat samples and using GPS collar data, Joel’s data, as well as studies done in urban areas, reveal many of the same items on both lists. Small mammals like voles, mice and rabbits are a large part of diets in both studies; and elk and other ungulates show up as a large part of the coyote diet only in the rural studies. Data from multiple studies disproves the common notion that the urban coyote’s diet consists mainly of trash, pet food and domestic pets. It also includes the variety of species depicted in this piece—the aforementioned mammals—but also birds, insects and plants/grass. The coyote is such a successful urban dweller because it is adaptable to the continuous human encroachment on wild spaces.

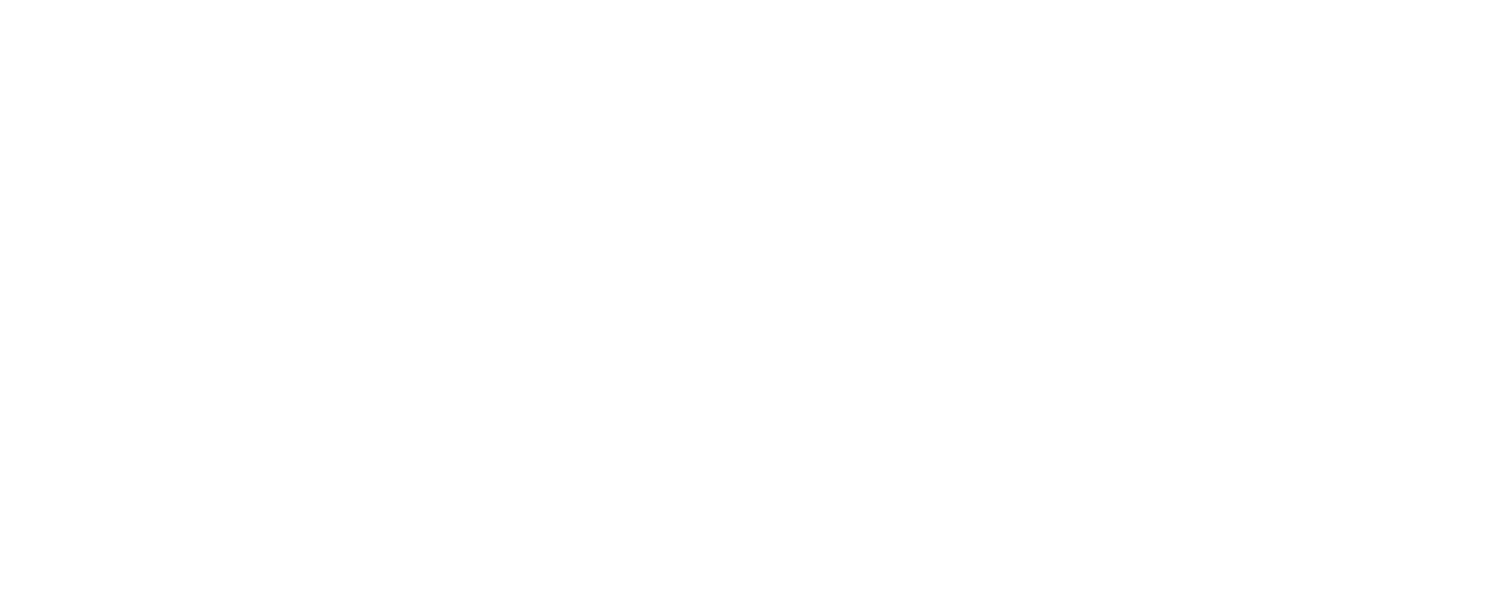

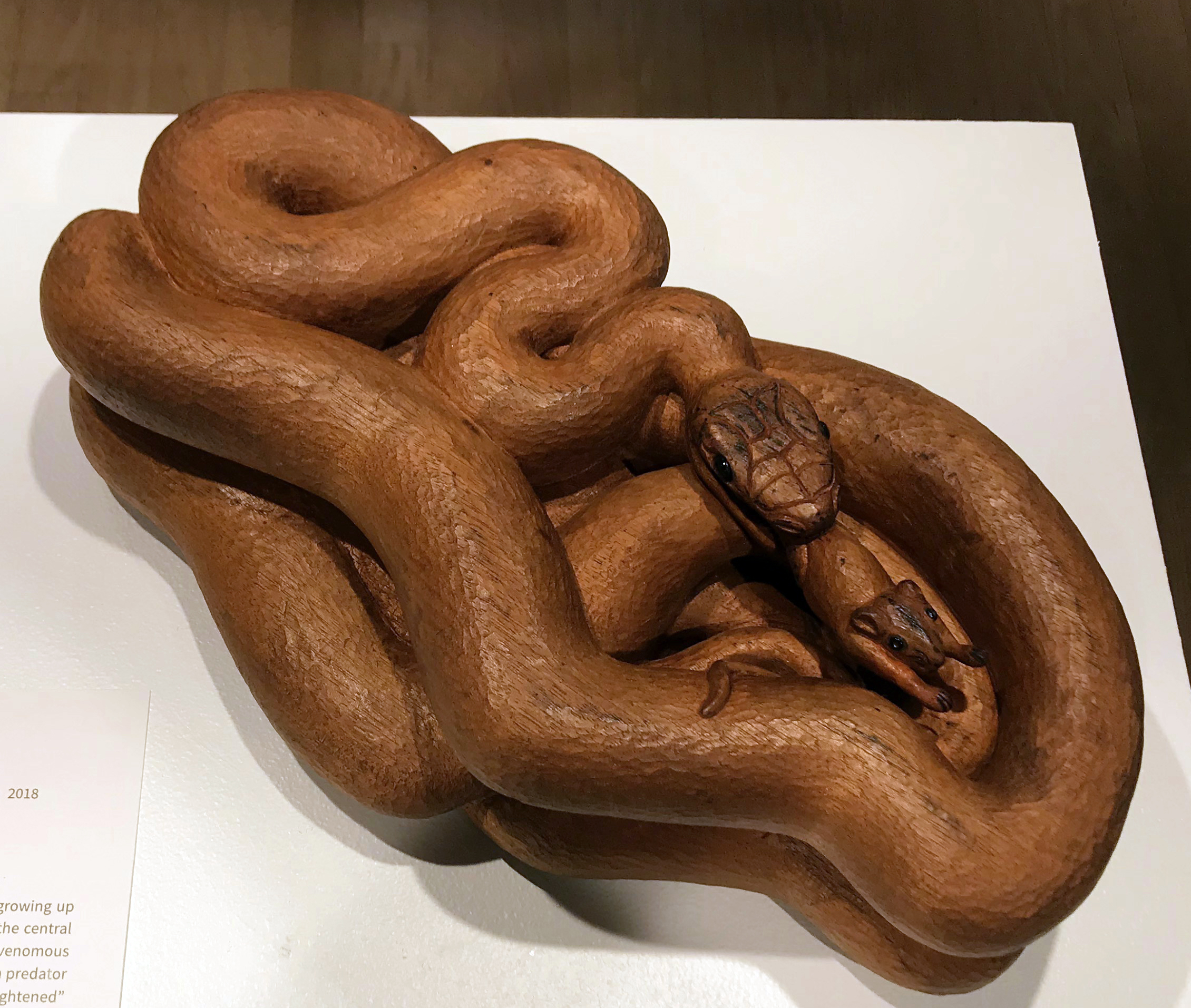

Snakes have been a constant presence in my life, growing up on Long Island, and in my current environment in the central Piedmont of North Carolina. Initially, I killed any venomous snake I encountered. I personally witnessed a shift in predator species balance in my own yard, after an “unenlightened” neighbor shot and killed a mature pair of black rat snakes in nearby trees. Up to this point, black snakes had been prevalent around our property, and we’d not seen any copperheads. Soon after, I was bitten by a copperhead in my yard, and subsequently had frequent nightmares involving snakes. A herpetologist friend convinced me to stop killing copperheads and altered my consciousness in dealing with them. Over the past several years, I’ve caught and relocated 10 copperheads.

Snakes are fascinating and sometimes frightening subjects to portray. Their undulating rhythmic forms stimulate many sculptural possibilities. I’m interested in the intersection of observable, “scientific” reality with myth, where poetic interpretations of nature can reveal fresh truths. For example, snakes typically devour their rodent prey head first, but my representation suggests a sequence when the fleeing mouse is captured, creating a visual succession of movement. The black rat snake devouring a mouse exhibits clearly an ecological cycle of balance in our natural universe.

Fish are some of our least visible urban animals. Though they use our neighborhood streams as homes, spawning grounds, and highways, their underwater world seems quite separate from ours. However, what happens in the water is often a mirror image of what’s happening on the surface. The things we put on our land, and specifically on our lawns, are what we put in our groundwater, streams, and aquatic wildlife. From pesticides to erosion, excessive lawn maintenance can have a serious impact on the delicate chemical balance of a river ecosystem.

In this piece, a stream takes the place of groundwater underneath a home, with cutthroat trout and caddis flies (an indicator species for ecosystem health) intermingling with the roots of a lawn full of native Western plants. By showing wildlife in a physically close relationship with a healthy lawn, I hope to call attention to how ecologically close our yard practices are to the health of our water systems. Here are some tips to help native trout populations: Consider changing your lawn from high-maintenance grass to attractive native plant species. Minimize your water use by choosing drought-tolerant plants. Avoid pesticides and herbicides, and trade out chemical fertilizer for compost.

I recently bore witness to a fox trotting purposefully past my neighbor’s picket fence, carrying firmly in its mouth a very plump squirrel. Living in the suburban town of Barrington, Rhode Island, I often see wildlife existing in our midst, but rarely so close at hand. The dichotomy of wild and tame struck me instantly. My piece is meant to explore the contrast of a wild creature against a controlled, manicured environment and ask the viewer to consider their comfort level with such a creature inhabiting, not just the woods and fields, but our own back yards. Do we feel empathy for the squirrel? What if the fox had a kitten in it’s mouth instead of a squirrel? My hope was to cast the fox, not as an intruder, but as a neighbor who must live along side us, sometimes in close proximity, as neighbors often live in urban and suburban environments.

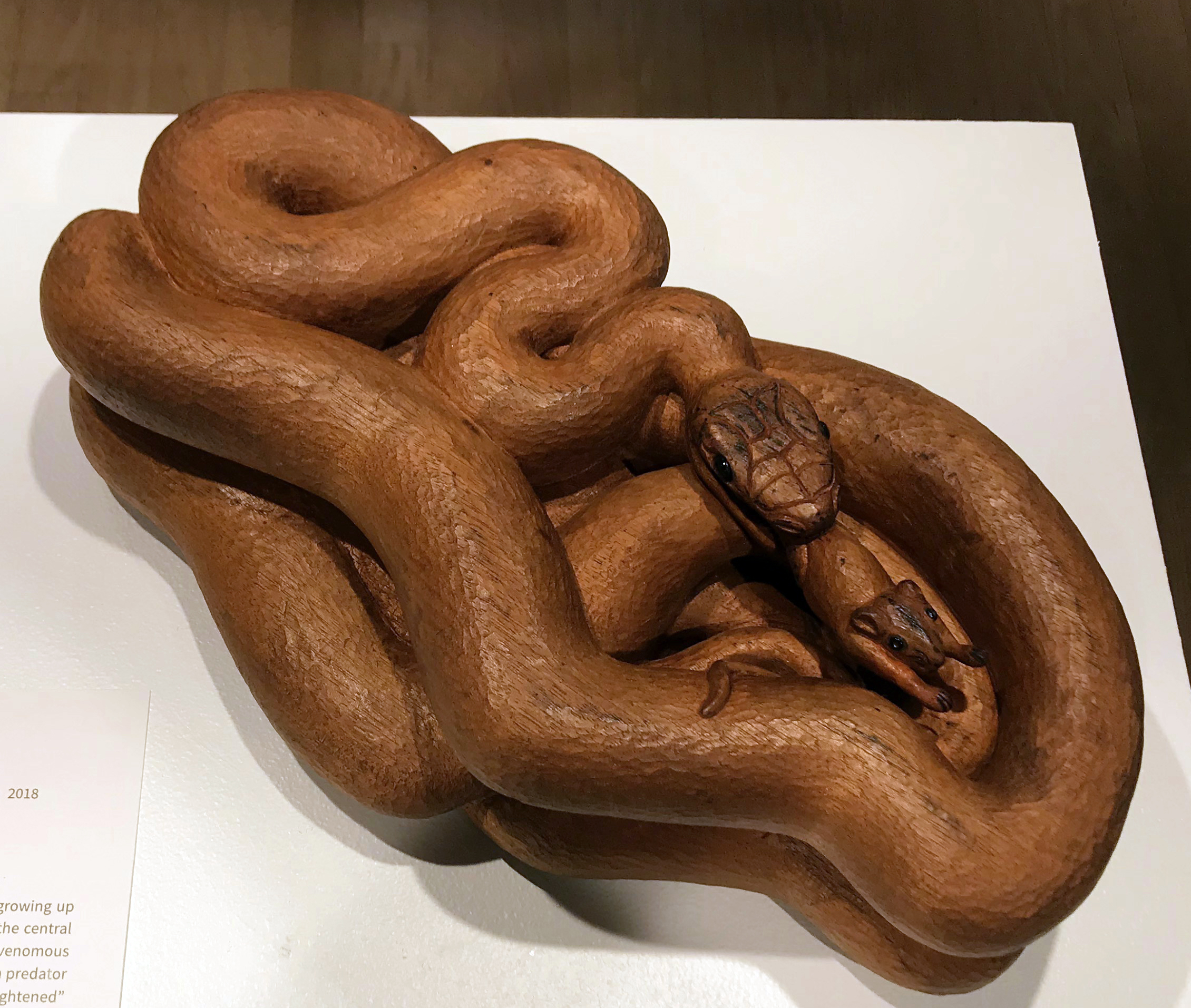

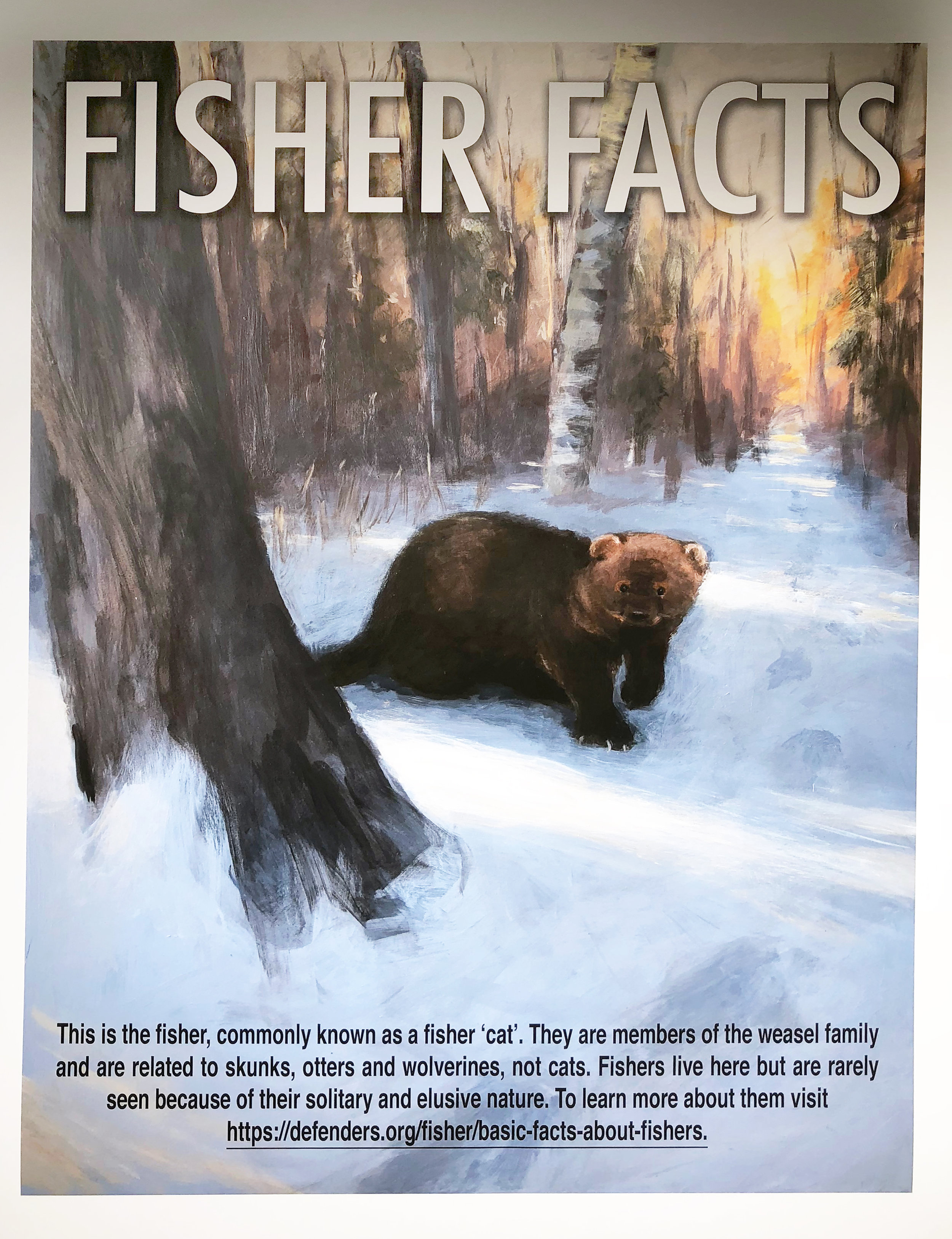

The fisher is generally a secretive and stealthy creature, which makes it an excellent predator; but one that is difficult to bring to public attention. Referred to colloquially as a ‘fisher cat’, fishers are actually the one of the largest members of the weasel family. Fishers are generally disliked because of their reputation for preying on pets and livestock and are often seen as nuisance animals. However, they are one of the few predators to actively prey on porcupines, a species that can be detrimental to forest growth if their populations go unchecked. Fishers are extremely important components of their ecosystems and are excellent indicators of environmental health since they favor healthy, old-growth forests with lots of canopy cover. Fisher populations are stable in most of Canada and the Eastern United States, however the population in the Pacific Northwest, struggle against natural, environmental, and anthropogenic factors. It is imperative that we create more visibility for this creature and maintain their habitat using by reinforcing and creating legislation surrounding responsible land use. The Fisher Facts poster is meant to inform and generate curiosity about fishers, hopefully changing their reputation by creating deeper understanding for fishers and their environment.

Rabbits are quiet, quick, and beautiful. I like their stillness. Their alertness. Their cottontails. Monty Python. Bugs Bunny. Pregnancy tests. Beatrix potter. Our native New England cottontail population is in trouble, the result of subsistence hunting in the early part of the twentieth century. In the 1930’s governmental agencies and local hunting clubs introduced the Eastern cottontail in efforts to restock local rabbit populations, possibly not realizing that the Eastern cottontail is a non-native New England species. Since then, the Eastern cottontail population has grown while the New England cottontail population has virtually disappeared. Currently there is a breeding program of New England cottontails at the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence aimed at reintroduction. There are also local habitat restoration efforts taking place in New England states. New England cottontails prefer early successional forest habitat.

These pictures document my encounters with rabbits that live in the unkempt overgrown wild thickets in my neighborhood. They are most certainly Eastern cottontails. There are cameo appearances by a plastic rabbit lawn ornament that I photograph with my family members every Spring, on Greek Easter, and a 118 year-old taxidermied New England cottontail from the RI Natural History Museum.

Special thanks to Charlie Brown at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, Matt Becker at the Museum of Natural History in Roger Williams Park, and Lou Perotti at the Roger Williams Park Zoo for sharing their knowledge about cottontails.

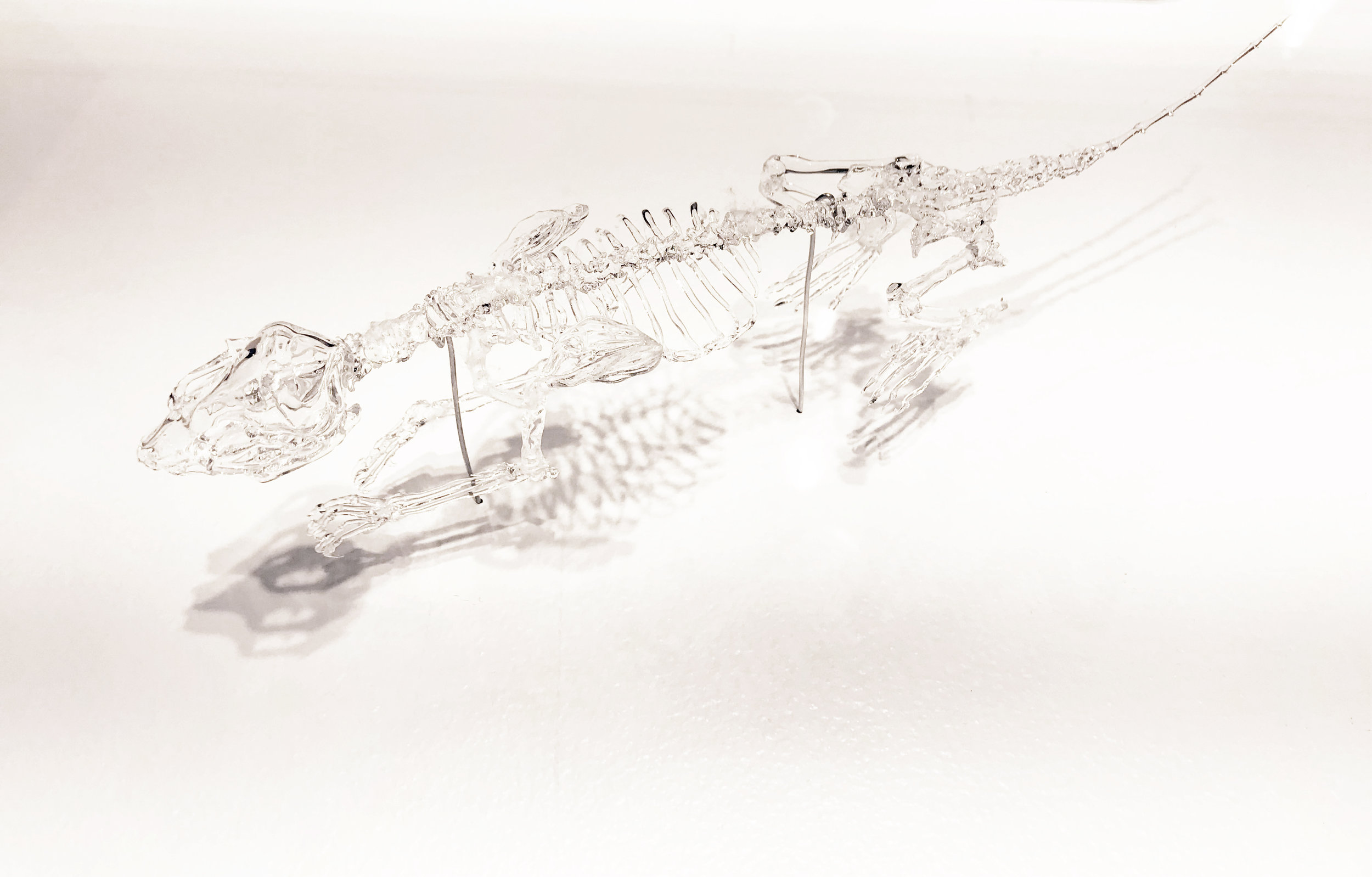

Merely existing among a city’s buildings, roads, and pollution is something of a superpower for wildlife. However, many reptiles and amphibians can indeed live and even thrive in urban areas. While numerous species have been decimated by the conversion of rural landscapes to the lawns, pavement, and buildings comprising our cities and suburbs, some species have taken those changes in stride.

This triptych highlights three such species: the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana), red-eared slider turtle (Trachemys scripta elegans), and green anole lizard (Anolis carolinensis). All are native to some part of the United States but have vigorously colonized far from where they originate. And all are frequently found in cities and suburbs, often aided by human activity and land development. For other species, like spotted turtles, wood turtles, whiptail lizards, western skinks, horned lizards, legless lizards, wood frogs, pickerel frogs, and western toads, pollution or asphalt can be insurmountable challenges. Animals like western pond turtles, red-bellied turtles, western fence lizards, red-legged frogs, and Asiatic toads are eaten by or cannot compete with urban bullfrogs, sliders, and anoles. These many species become ‘ghosts’ — depicted as silhouettes in the triptych — relegated to tiny patches of suitable city habitat or the urban fringe, their presence overshadowed by the others’ success.

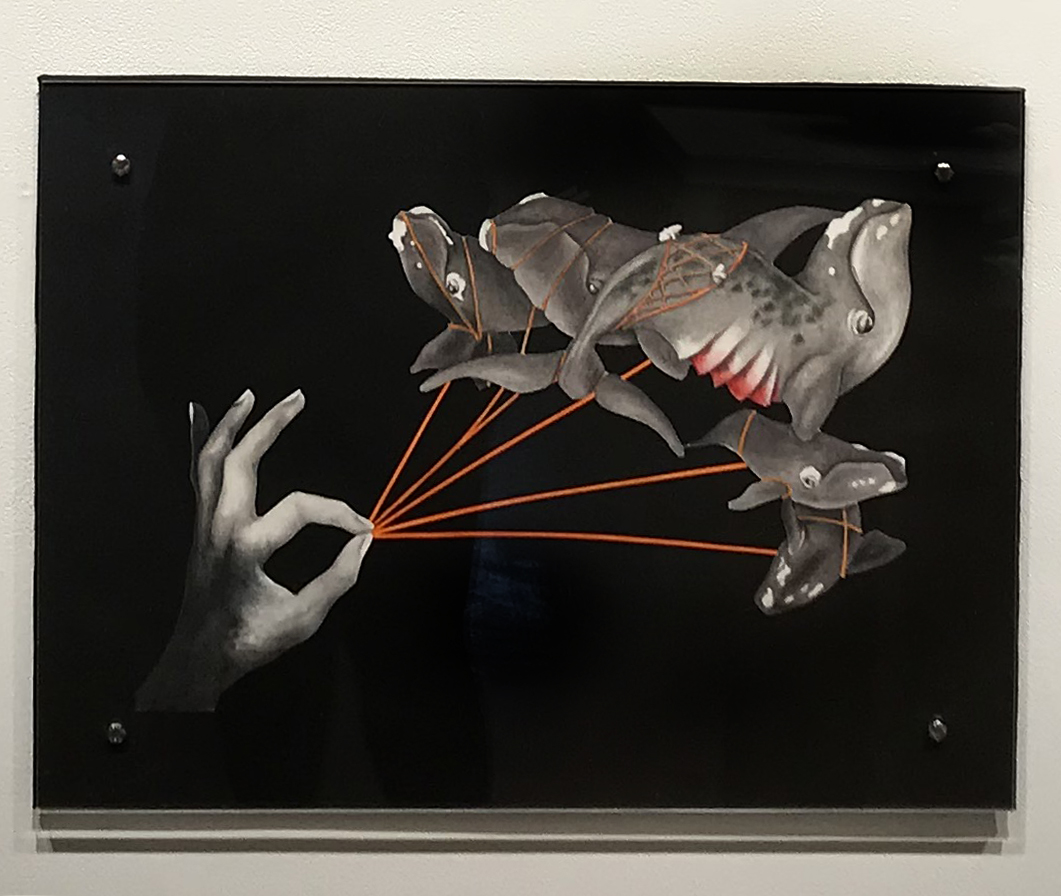

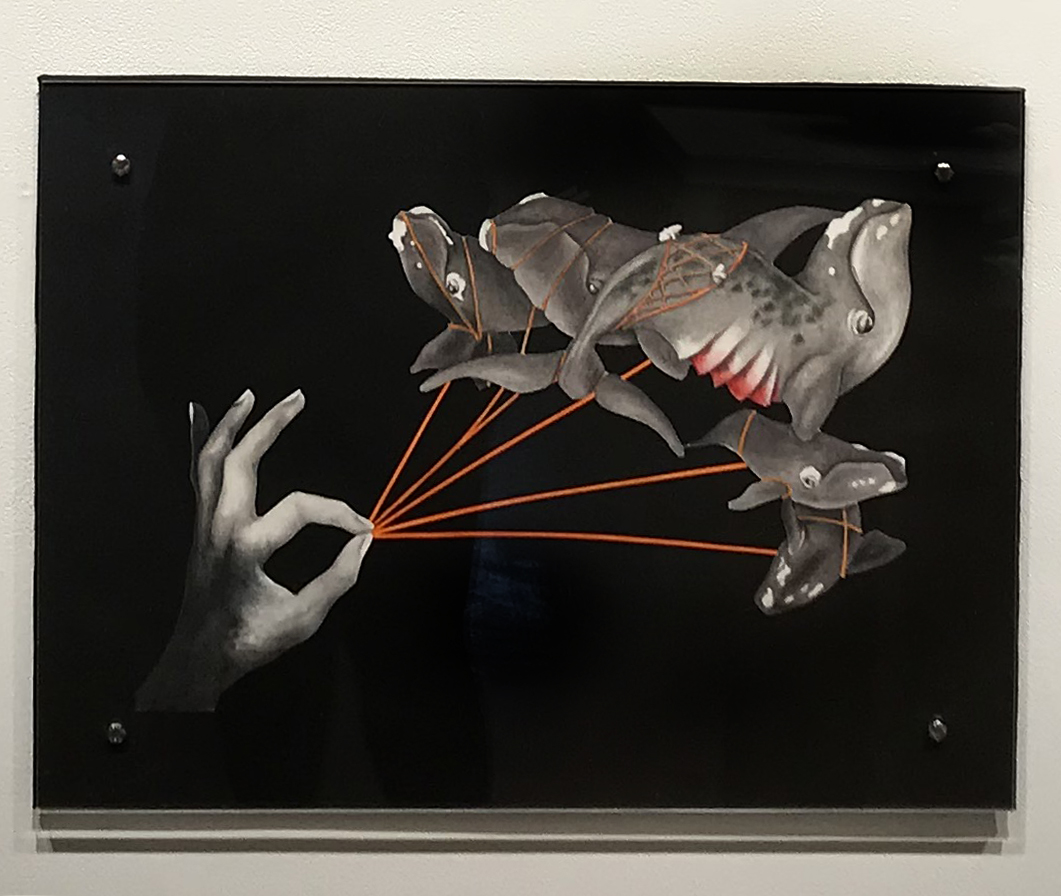

Off the shoreline of the Atlantic northwest, the whir of the Anthropocene is deafening. The whale songs that once echoed off the cliffs at the Bay of Fundy and the beaches of Cape Cod, are mostly gone, replaced by the slow churning of the sounds of our machines. The once plentiful playground of the North Atlantic Right Whale is barely recognizable. What was once a population of tens of thousands of whales has been hunted almost to extinction, now reduced to an estimated 460 individuals. Recent conservation efforts have brought this species back from the brink of extinction along the Atlantic coast of the US and Canada; over the past fifty years their numbers have doubled with the aid of governmental restrictions on boat speed and whaling. Although these efforts have been monumental, they have not been enough to stop the inevitable: extinction. Increases in noise pollution, fish net entanglement, and ship strikes, paired with a recent decrease in birth rate, paint a picture of future devastation. The fate of the North Atlantic Right Whale is in the hands of us, the people who have the ability to actively incite change, or not.

“Signaling Trouble” is a series of artworks depicting the plight of the North Atlantic Right Whale, as it faces potential extinction. Migratory patterns bring the whales close to the eastern US and Canadian shorelines, first off the coasts of Florida and Georgia during calving season, then feeding on copepods in Cape Cod Bay, Gulf of Maine, Bay of Fundy, and in the last two years St. Lawrence Bay, earning them the nickname “urban” whale. The major causes currently threatening their survival, including ship strikes, fishing gear entanglements, as well as rising sea temperatures, are referenced within this series. Original graphics, along with images from the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog, are combined with international maritime signal flags enabling the whales to speak directly to viewers. The series aims to raise awareness to their situation, encouraging viewers to help protect this endangered species and the waters they inhabit.

I Require Your Assistance

I Require Medical Assistance

You Are Running Into Danger

I am Disabled. Communicate With Me.

I Wish To Communicate With You.

Keep Clear of Me

I am Altering My Course

Permissions were granted for use of specific whale photographs by Heather Pettis, Research Scientist and executive administrator for the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium. Consultation to review the artworks for accuracy and appropriateness was conducted with Research Scientist Philip Hamilton, from the Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life at the New England Aquarium.

Once a common species, the range of the New England cottontail has decreased by 80% in the last 50 years due to habitat fragmentation caused by suburban sprawl. New England cottontails thrive in habitats in the stage of early succession, which follows both deforestation (due to either clearcutting or natural disaster) and agricultural abandonment. These conditions are common on privately owned property - therefore, the restoration of their population calls for cooperation between property owners to create corridors of native vegetation that both shelter and feed enough New England cottontails to ensure a lasting population; anything less than 12 acres will not support more than 3-4 rabbits. Autonomy over land comes with a responsibility to be aware of the ecosystems that extend beyond property lines. Retention of shrubland and overstory forests of sufficient size can be achieved with cooperation between private landowners and the many conservation services and organizations (such as Center for Conservation Incentives and the Natural Resources Conservation Service) that are willing to help them prevent the extinction of the New England cottontail.

The artist collaborated with scientist Dr. Pam Dennis (Cleveland Metroparks Zoo) identifying the following study performed in their local area, Cleveland Metroparks: “Humans and urban development mediate the sympatry of competing carnivores” (Moll, Cepek, Lorch, Dennis, Robison, Millspaugh, Montgomery). The study involved a dominant-subordinate carnivore pair in conflict - red fox and coyote. In the wild, red fox populations are declining in areas where coyotes are moving in. But urban development may actually facilitate the coexistence of the two species. In Cleveland Metroparks, an urban/suburban park system, red fox appear to avoid conflict with coyotes by using humans as a shield. The coyotes (dominant carnivore) strongly avoid human interaction and retreat to rural spaces while the red foxes (subordinate carnivore) tolerate humans and choose to inhabit developed residential areas. The artist’s interpretation was to create a tessellating pattern of coyote and fox to illustrate their co-existence without conflict. The pattern was hand-carved and stamped on fabric as a wearable piece/scarf: the two species separate on the ends and come together where it would wrap around a person's neck, indicating humans facilitate their situation.

The Providence Raptors collection features the city’s wild birds of prey, perfectly at home among the landscape of brick and steel and concrete. Regal and streamlined Peregrine Falcons have nested continuously on the “Superman Building” art-deco skyscraper since 2000 and have successfully reared 55 offspring. Red-Tailed Hawks, the most common local raptors, often perch high up on The Independent Man for a 360° view from atop the Rhode Island State House. Small and colorful American Kestrels are natural rodent control and visit the industrial shoreline looking for mice and other critters to consume. Ospreys are the bird world’s champion anglers and can be spotted all summer grabbing fish from the Seekonk River. By documenting and studying how these adaptive predators live in our urban world, we can make adjustments to how we live to help ensure they survive and thrive.

These two paintings were inspired by urban coyotes and their interactions with humans. They imagine a representation of an ideal urban setting that has natural green spaces for humans and coyotes to thrive in. An ideal coyote green space would limit the coyote's interactions with humans to prevent habituation. Urban coyotes have adapted to human daytime activity, resulting in their being active at night. I see these two worlds as being contained and separated within one city, aiding in their coexistence by limiting potentially negative interactions. Special thanks to Dr. Numi Mitchell for sharing her coyote knowledge and for doing all that she does to help us co-exist with these animals in Rhode Island.

I live in northwestern Wyoming, within the region known as the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. I share this space with humans and wildlife.I am inspired by the wildlife biologists, scientists and wild land managers who through education and community outreach have presented compelling information about the wildlife that live and travel in and out of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. One of the migration routes of Pronghorn antelope traces a path from the Red Desert, their winter range in south central Wyoming to their summer range near the Tetons in northwest Wyoming.I want to describe this landscape from a perspective that speaks to the austere beauty and openness of the sage flats of the Red Desert as well as the manmade impediments along the migration route that fragment and degrade this corridor, threatening the survival of the antelope herd and all who live on it. As an illustrator I work with images to tell a story and using the transparency of watercolor to show the layers of reality and conflict between human development and wildlife.Through this lens of mutual uses and needs I hope there are ways of seeing compatibility that offer success to all species.

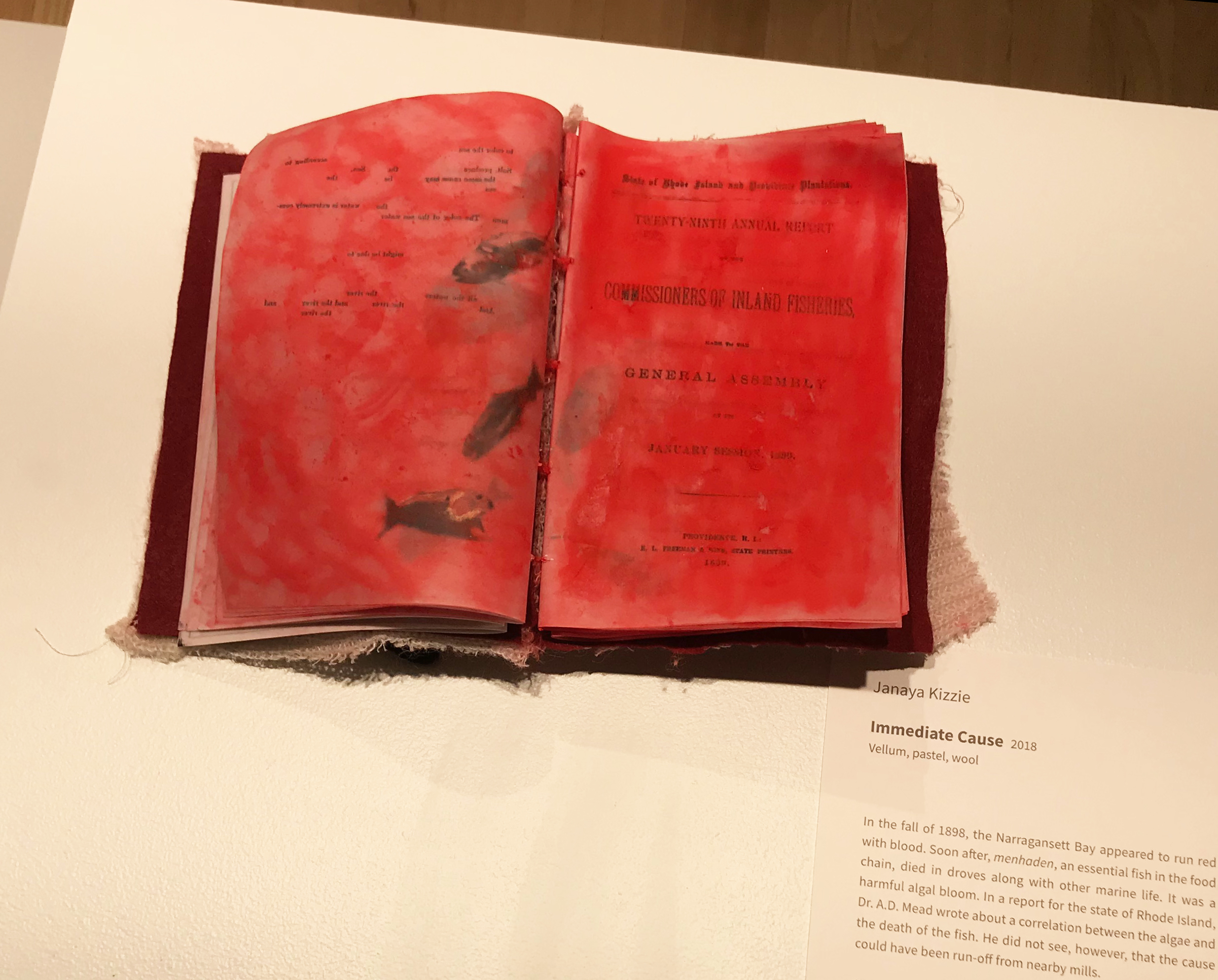

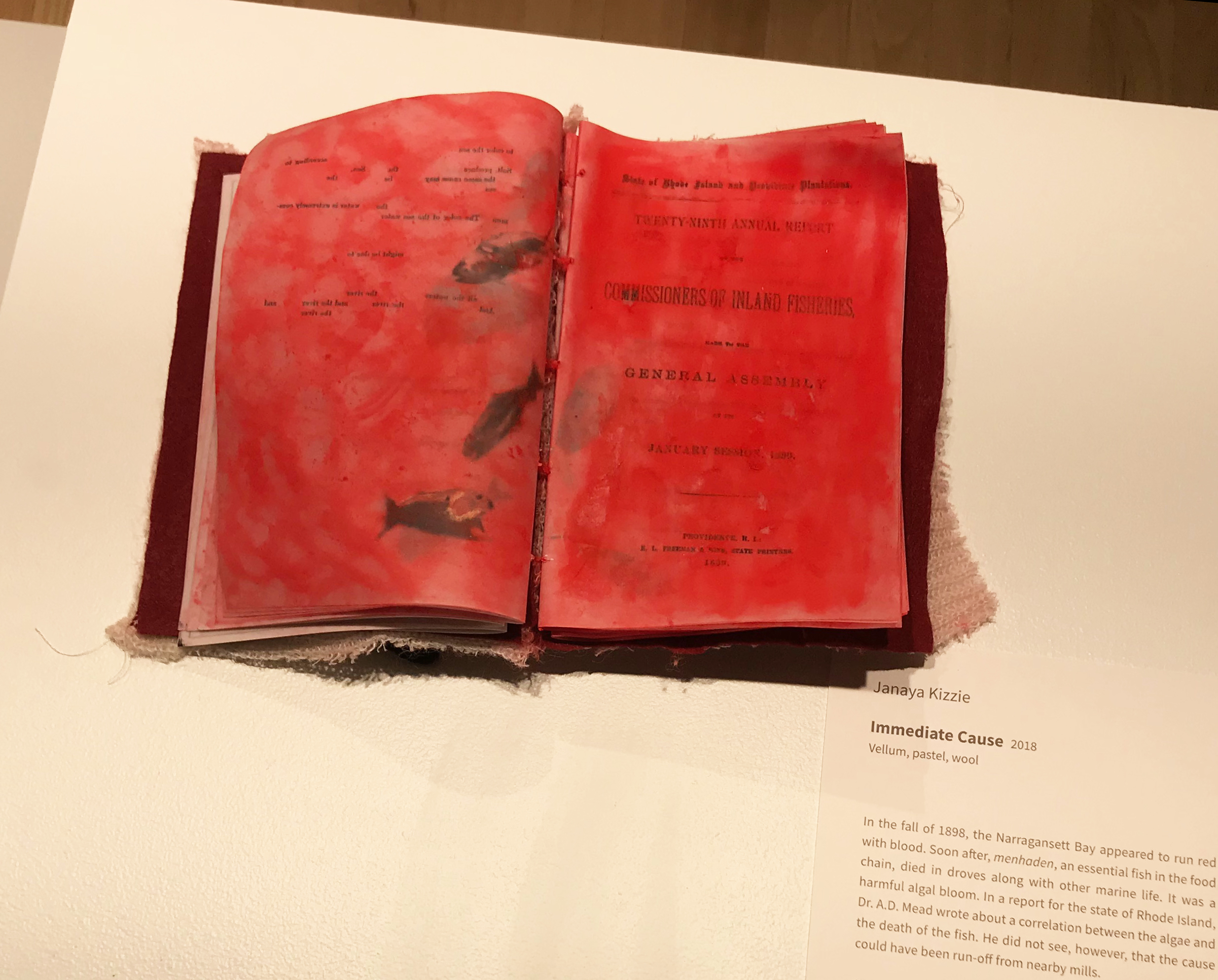

In the fall of 1898, the Narragansett Bay appeared to run red with blood. Soon after, menhaden, an essential fish in the food chain, died in droves along with other marine life. It was a harmful algal bloom. In a report for the state of Rhode Island, Dr. A.D. Mead wrote about a correlation between the algae and the death of the fish. He did not see, however, that the cause could have been run-off from nearby mills.

Our daily lives, so different , but not separate, can push the dance between algae and aquatic life into its extremes. Small changes in water pH and temperature caused by local dumping can cause algal blooms which either poison or suffocate the menhaden. The relationship is not cause-and-effect, not “immediate cause” as Dr. Mead put it, but more complex.

I reduce Dr. Mead’s report, “Investigations of a plague which destroyed multitudes of fish and crustacea during the Fall of 1898” in two ways: an erasure of the text, and the slow obscuring of the words by illustrated red algae. Wool, evoking worsted spun at Rhode Island mills, envelop the text, and illuminated menhaden, martyred by the bloody water, dance in the margins.

I find that beauty and travel are the inspirational elements in my creativity and life. In my photographic work of butterflies, I am intrigued by the various stages of their life, and the fact that the monarchs in this part of the world live without borders spanning Canada, the US, and Mexico. I offer to you the beauty and exquisiteness of the world around me that I experience. Right now I am captivated by the monarchs! Where did you last see one?

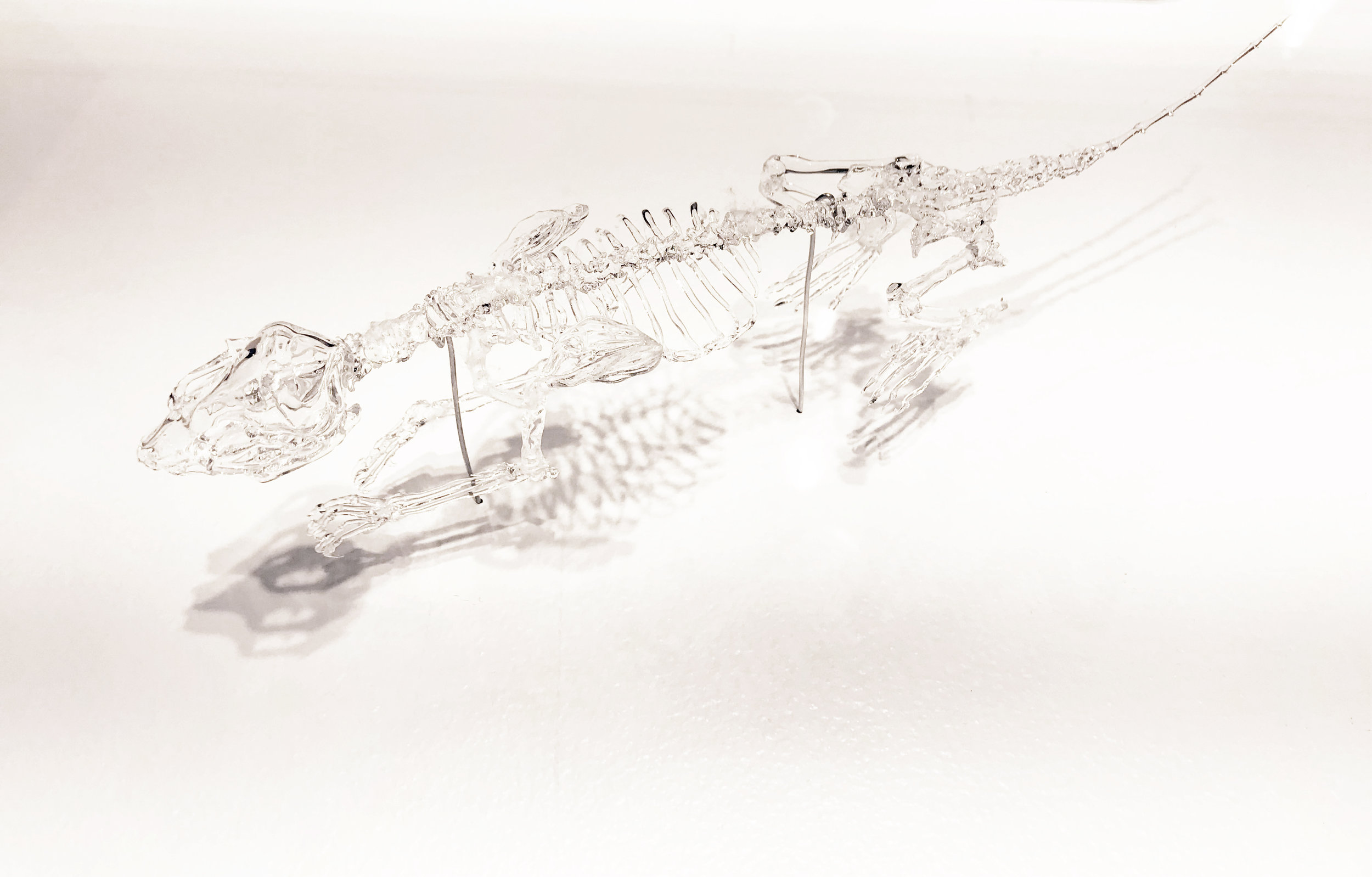

In response to a recent visit to Sunderland, UK, this project is a commentary on humans and their collateral effect on the natural equilibrium of life. It seeks to raise or preserve awareness of the fragility of living things that have existed through time. Since the Age of Exploration, human inclination to explore unknown parts of the world has undoubtedly impacted local biodiversity; diminished and or diversified species in all parts of the earth. "The Two Partners for Life" speaks about the adverse effects of human migration and its undeniable affect on local flora and fauna in introducing creating a number of new invasive species, such as the North American grey squirrel. Sciurus carolinensis, the eastern gray squirrel is a species introduced to Great Britain from North America in the 1870’s. It has not only invaded the local the region in the UK, but consequently also depopulated the local red squirrel, Sciurus vulgaris. Since grey squirrels are carriers of the Squirrel pox virus, a malady that the red squirrels has no immunity to, a sharp decline of the beloved red squirrel was inevitable. This anatomical study highlights the possibility for all things to coexist; for two species from the same genus to breed, unite and evolve as ‘sciurus carolgaris,’ rather than to threaten either one's existence.

The hallmark of the new geological era of the Anthropocene is the visibility of the human impact on the climate, the environment, and every living thing on Earth. The hierarchical view of nature that has pervaded scientific inquiry since the age of Aristotle has allowed humans to tell a story in which domination of the planet and all forms of life is the standard of achievement. This story can be seen in the evolution of the ancient rock dove into the oft-reviled city pigeon. From Noah’s dove to today’s racing birds, we have used pigeons for everything from recreation to communication to sustenance. But when and why did we cease to worship the bird for its incredible skills and begin to consider it a lowly pest? Through an ethnography of human/pigeon culture conducted in Boston, Providence, and New York, I documented the past and current narratives of the ubiquitous bird, which allowed me to muse on the story of its future. How will climate change, pollution, and human overpopulation continue to influence the evolution of this once beloved bird and our perception of it? And how can we reimagine the future to include space for the resiliency of all creatures?

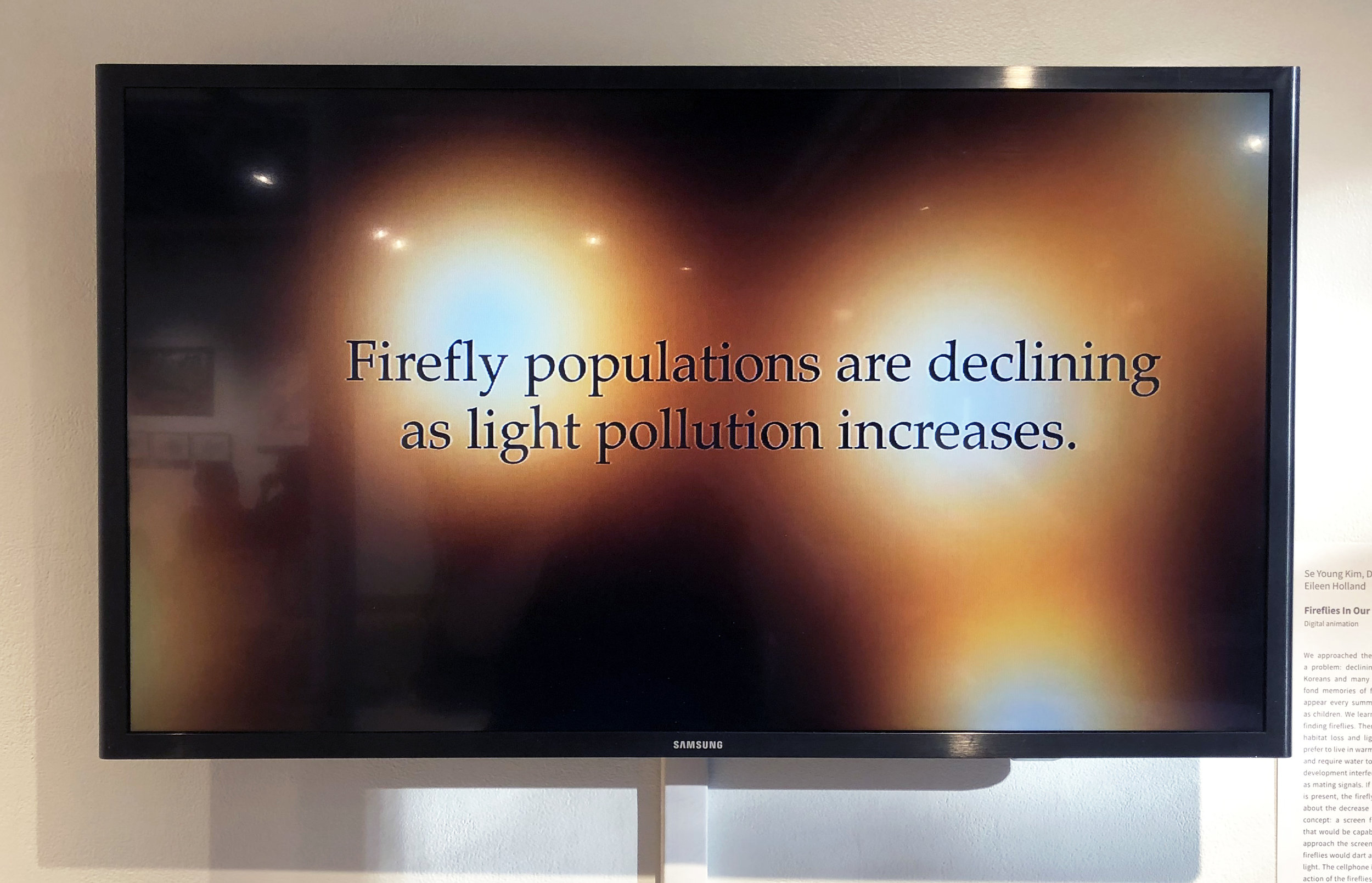

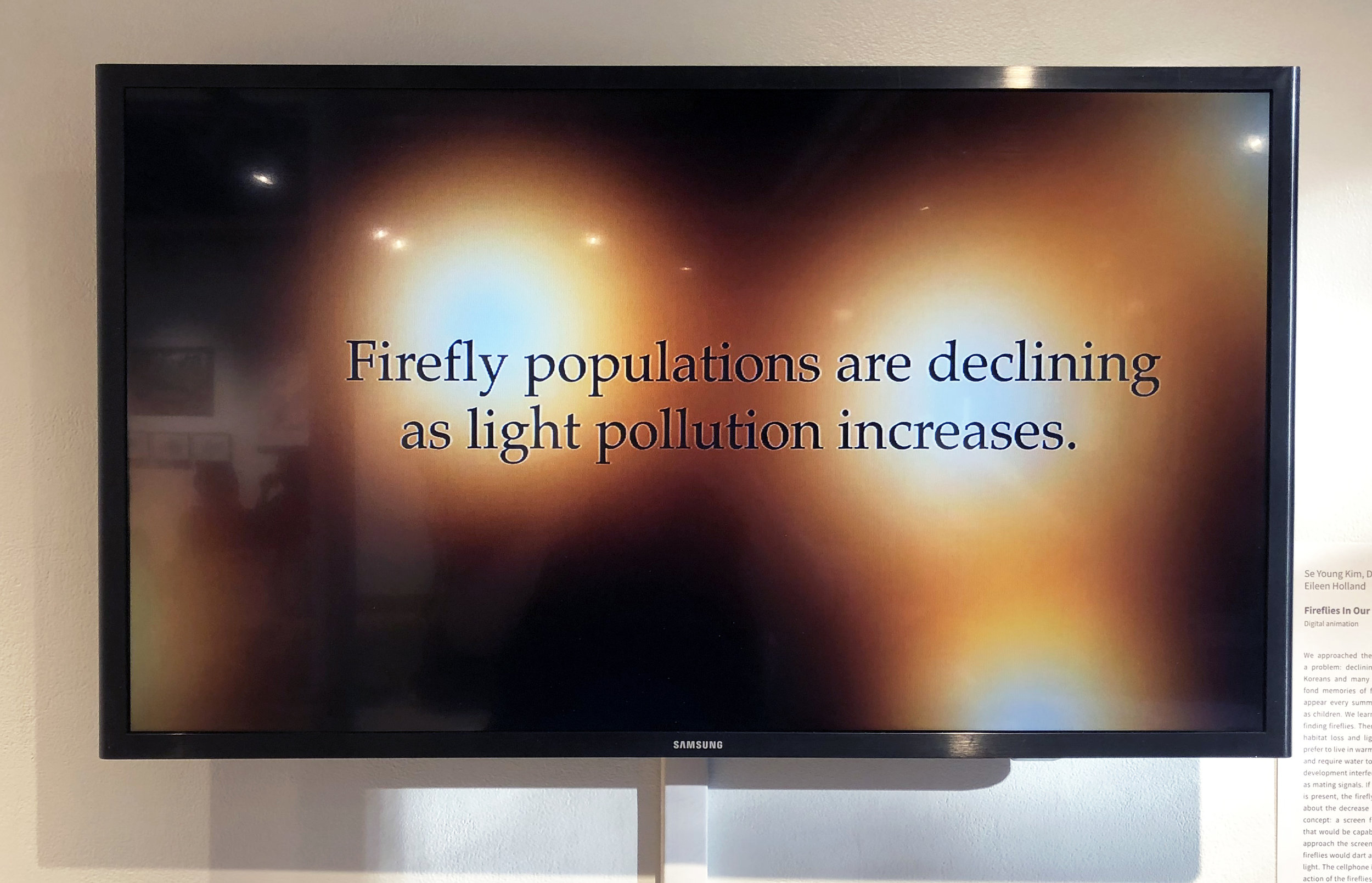

We approached the urban wildlife project by researching a problem: declining firefly numbers. We found out that Koreans and many people in many other countries have fond memories of fireflies: beautiful twinkling lights that appear every summer. They remember playing with them as children. We learned that people are now having trouble finding fireflies. There are two main reasons for the decline: habitat loss and light pollution. Fireflies are beetles that prefer to live in warm, damp, open areas near standing water and require water to reproduce; light pollution from human development interferes with their flashing lights which serve as mating signals. If a light source brighter than a full moon is present, the firefly does not light up. To raise awareness about the decrease in fireflies, we developed the following concept: a screen full of fireflies with a sensor attached that would be capable of detecting moving light. When you approach the screen, if you wave your cell phone at it, the fireflies would dart away to simulate the impact of too much light. The cellphone is a metaphor for light pollution and the action of the fireflies scattering away is a message about the decrease in firefly population because of human activity.

Snowy owls are urban creatures, at least part of the time. While they spend their summers in the arctic far from any human interference, many snowy owls irrupt south in winters and end up in surprising urban environments- rooftops, populous beaches and most interestingly, airports, where the terrain mirrors their tundra habitat (wide open spaces, lack of trees, good forage). It helps that this past winter was an irruption year and snowy owls could be found all over the east coast. I had seen 8 individual owls in the wild this winter, everywhere from backyards and hotel roofs to jet runways a few hundred feet from moving aircraft. In Portland, Maine this winter there were as many as 6 owls using the airport, and it became a source of consternation for airport security as birders flocked to see and photograph this mysterious visitor from the north. How did they get here and why do they keep returning? I was fortunate to be able to partner with Scott Weidensaul and the field biologists who work with Project SNOWstorm to find out. Project SNOWstorm researches the annual movement of these owls through transmitters that track where and when the birds travel on their southern explorations. It's a fascinating ongoing study, and timely because the snowy owl has just been listed as a threatened species, with the climate crisis as the main factor in their decline

Two years ago I moved to Sydney, Australia from NYC and was amazed at how integrated the city is with nature. There is a huge variety of wildlife that lives in Sydney that is present in the everyday lives of Sydney-siders.In Australia, birds are the main pollinators and essential for the health of Australia's ecosystem. There are over 400 birds in the greater Sydney metro area, however, due to habitat loss and invasive species, there has been a shift in which birds are thriving and which are at risk. One painting shows birds that are thriving and the other shows birds that have either disappeared or are declining due to urbanisation. Dr. John Martin, zoologist at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney was the collaborating scientist on the project. The result of our collaboration was the identification of birds both thriving and those that are in decline or disappeared. The birds are all painted without their habitat along with butterflies and insects that are also declining or thriving here. For the declining birds, the blank background shows their habitat as literally erased. And for the painting of the thriving birds, the blank background isolates them as success stories.

Domesticated cats are responsible for the deaths of over a billion wild birds each year. This has led to the extinction of several bird species native to certain islands and the addition of several others to the endangered species list. Many Americans feel as though cats are harmless and that allowing them to wander outdoors is healthy. But outdoor cats have a huge impact on local fauna. Even if the cat is well-fed at home, it will instinctively and sometimes playfully hunt birds and small mammals, leading to countless deaths. If pet owners continue to allow their feline companions free access to the out of doors, we may very well see the disappearance of once common native bird species from our backyards. Tarot cards are often used as a way to think about the past and the future. This piece uses the iconography from three major arcana cards to communicate the problem of cats now and in the future.

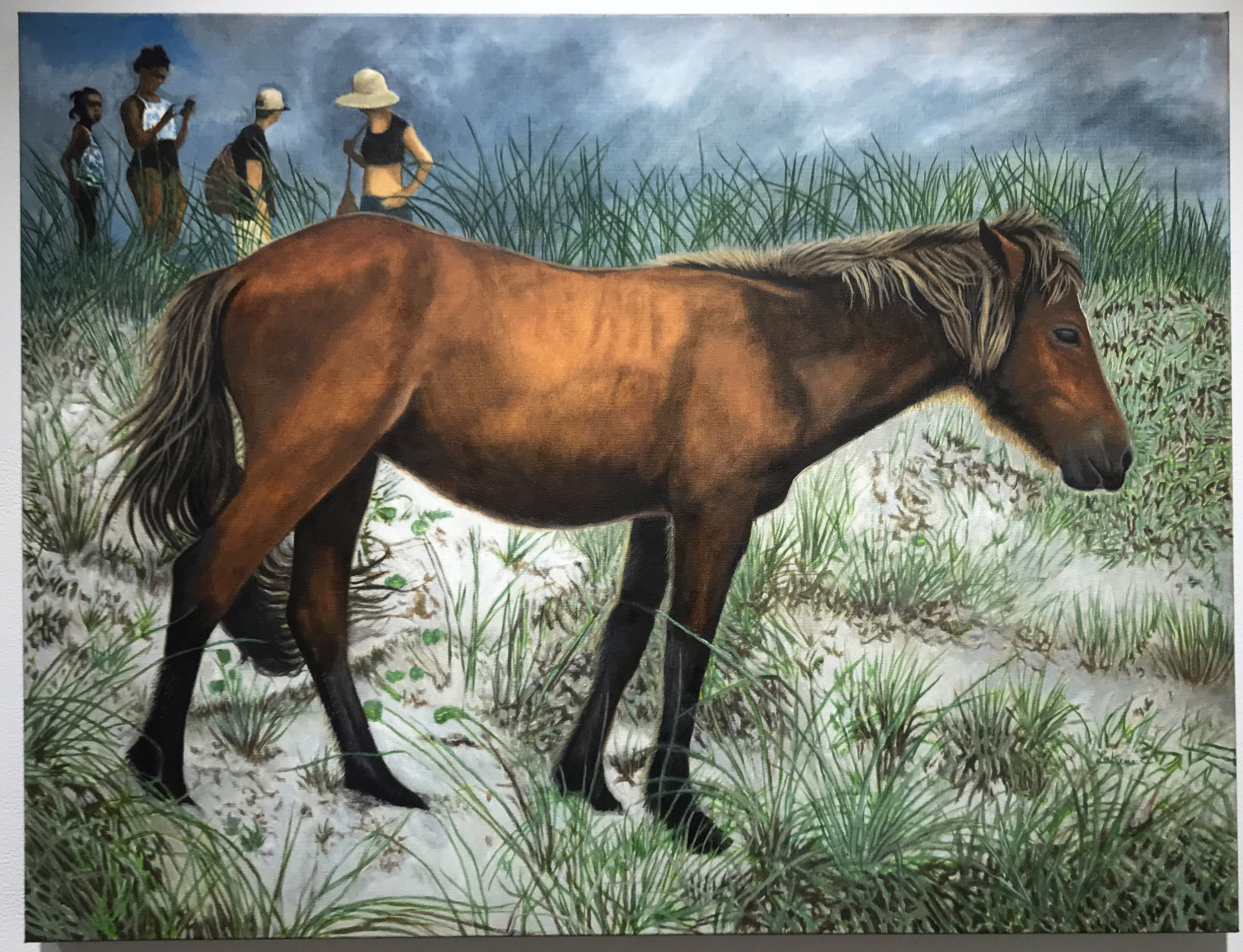

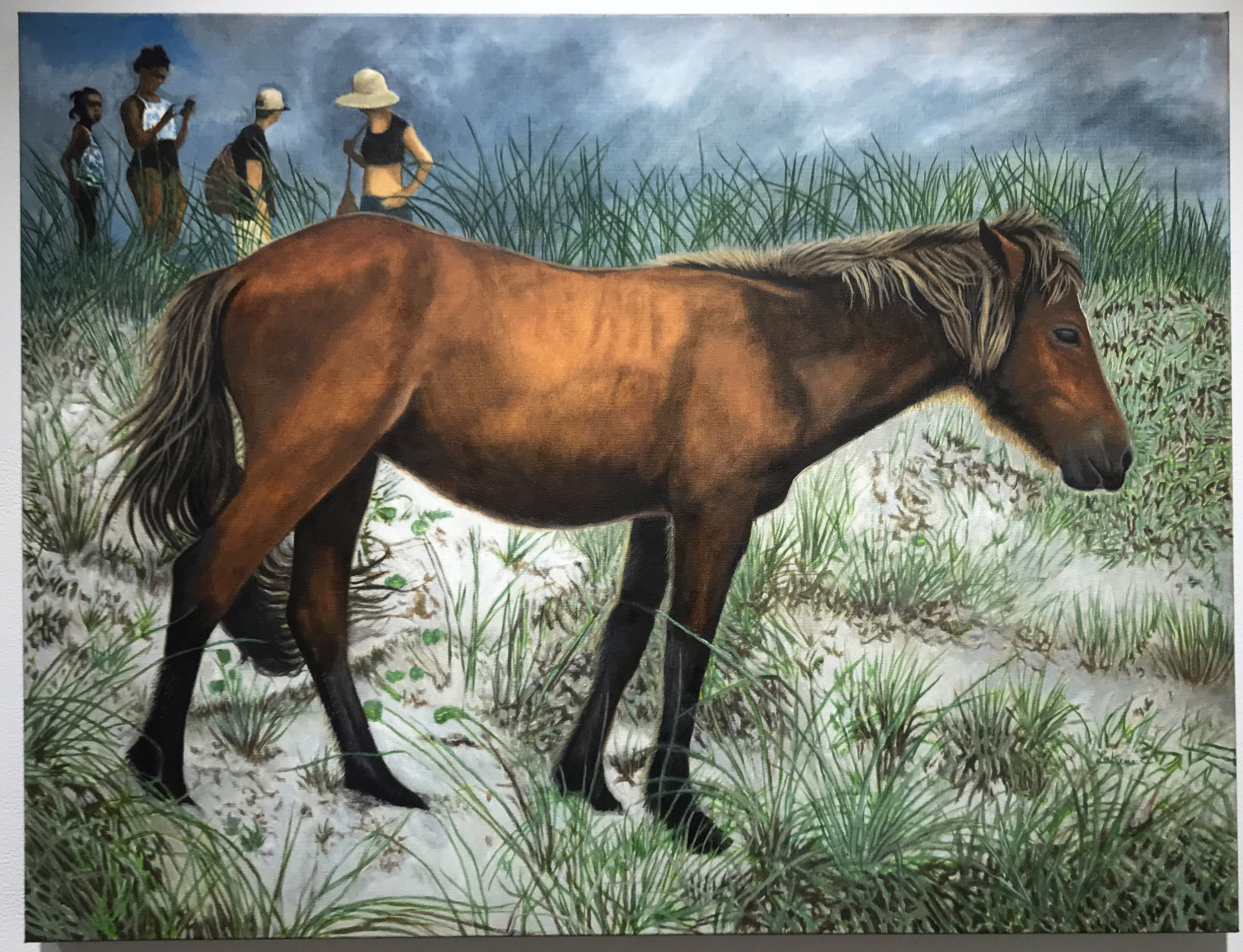

For this art/science project, I took the National Park Service ferry the 2 miles out to Shackleford Banks from Beaufort, NC, to find reference for my painting. Genetic testing has determined that the wild horse herd on S.B. are Colonial Spanish horses that may have originally survived shipwrecks off the treacherous Outer Banks in the 16th century. Their situation is unique, in that S.B. is their island. The last human occupants left over a century ago, due to hurricane devastation. The horses are managed by Cape Lookout National Seashore & the non-profit Foundation for Shackleford Horses. They find their own food (cordgrass, spartina, sea oats, & paniculata) & fresh water, as well as their own shelter from hurricanes, as provided by the maritime forest (live oaks) & thick shrubs on the north side of the island. The only human interference, other than unruly tourists (feeding, touching, teasing, frightening, or intentionally disturbing the horses is illegal & punishment is severe), is the culling of the herd by the N.P.S. to insure the herd does not exceed the maximum number that the island will sustain (130). Younger adult horses are captured & either placed in other coastal wild horse herds, or adoptive farms, for which there is a wait list. Selected mares are also contracepted on a year by year basis. The result is that we co-exist with our so-called wild horses.

Power lines are recognized as one of the leading causes of bird mortality. They have the potential to cause fatal injuries to birds; as a result of both collision an electrocution. They can also result in habitat loss; with certain bird species avoiding areas where powerlines occur. Power lines are a significant cause of mortality for Trumpeter Swans. They are a heavy-bodied bird that needs plenty of room for takeoff and landing. Through the use of bird diverters, devices attached to power lines to make them more visible, the hazards can be significantly reduced. These bird diverters have been put in place to keep a portion of the Greater Yellowstone's wintering Trumpeter Swans out of harm's way. The Teton Regional Land Trust along with the Fall River Rural Electric Cooperative worked to place bird diverters on power lines frequented by Trumpeter Swans. This painting shows the relationship of the Trumpeter Swans to the power lines when in flight.

Once abundant across North America, Trumpeter Swans were hunted for their hides and father. By the early 1900's they were thought to be extinct. In 1932 69 were found at Rod Rock Lakes, Montana, only another 2000 were found in Alaska. Swift conservation efforts have stabilized the population. The Teton Regional Land Trust has worked with families and other conservation groups over the past 25 years to conserve over 33,000 acres in East Idaho, including 11,000 acres in Teton Valley. The Land Trust teamed up with various groups to release Trumpeter Swans onto a protected wetland in an attempt to establish a nesting population.This painting depicts the exuberance of the 2018 Trumpeter Swan release. Two young Trumpeter Swans were released with hopes they would bond to the area and continue to return to Teton Valley to lay their eggs.

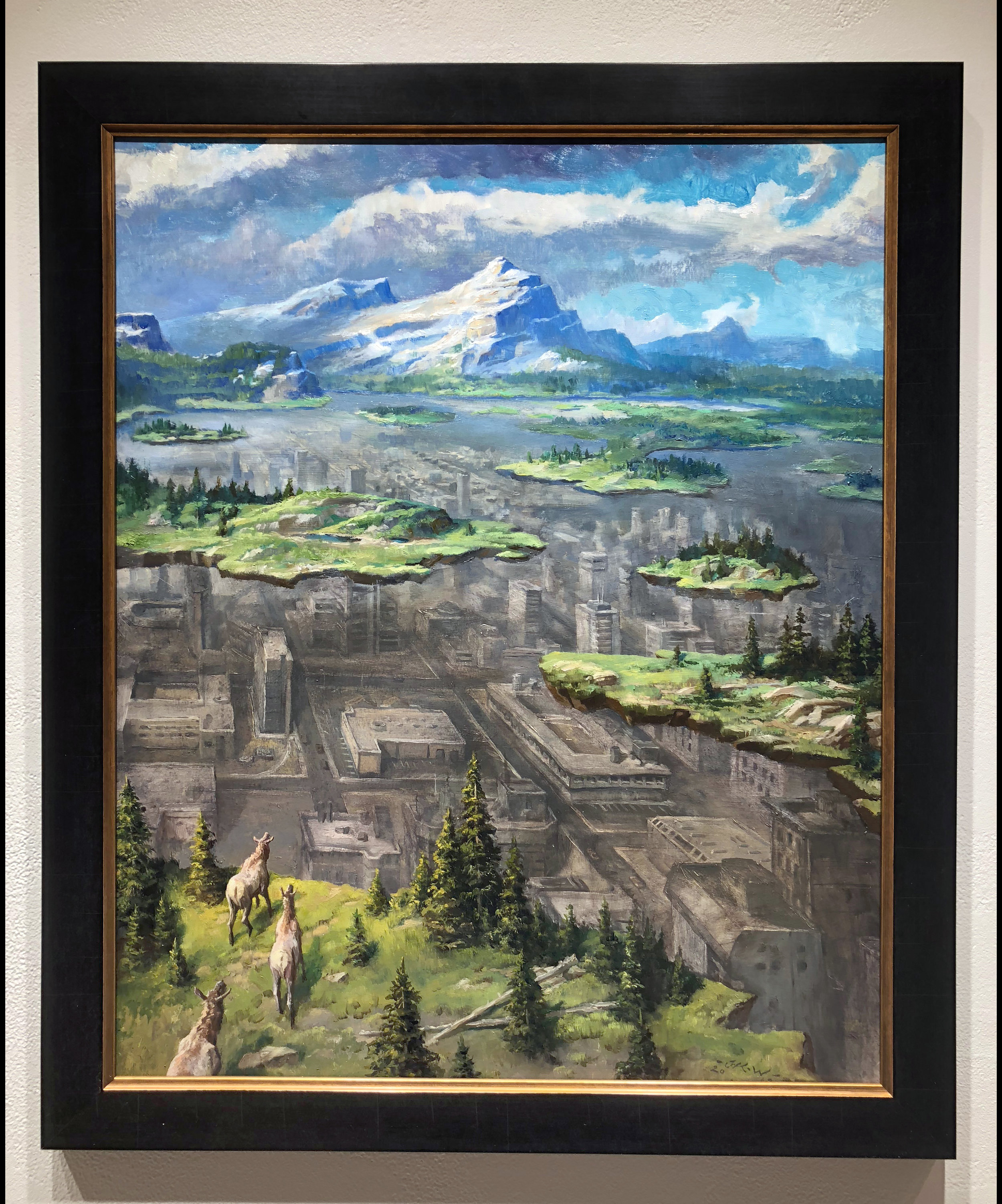

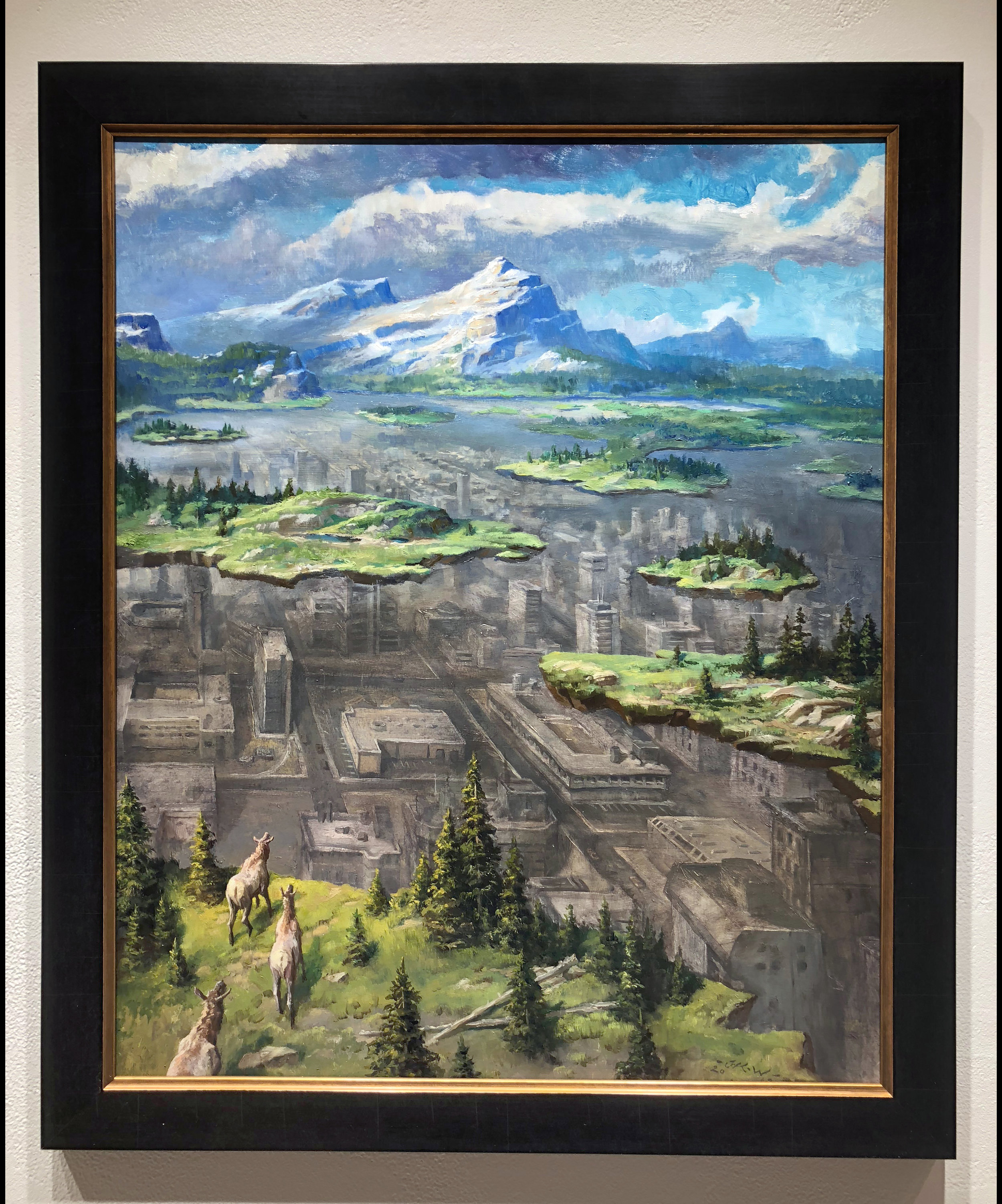

In the Western United States, a variety of ungulates including elk, bison, and mule deer follow seasonal migratory paths known as migration corridors that can stretch for hundreds of miles. These animals neither know nor care about the human made international borders they travel through, yet our ever increasing population and urban development has a profound impact on their lives. The urban sprawl across Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming has spread into and completely engulfed hundreds of traditional migration corridors these animals once relied on. In such an environment they put themselves at risk to collisions with oncoming vehicles and other human created dangers, and themselves pose a danger to people in the community. The few open migration corridors used by large ungulates that remain in the American West are under the constant threat of development by industrial and residential interests. Some potential solutions to this problem include wildlife overpasses and underpasses that allow animals safe passage across highways, but those that currently exist are few and far between. While pockets of wild spaces remain, they are often isolated and it is impossible for traditionally migratory animals to bridge the gap and travel in awe inspiring herds as they once did.

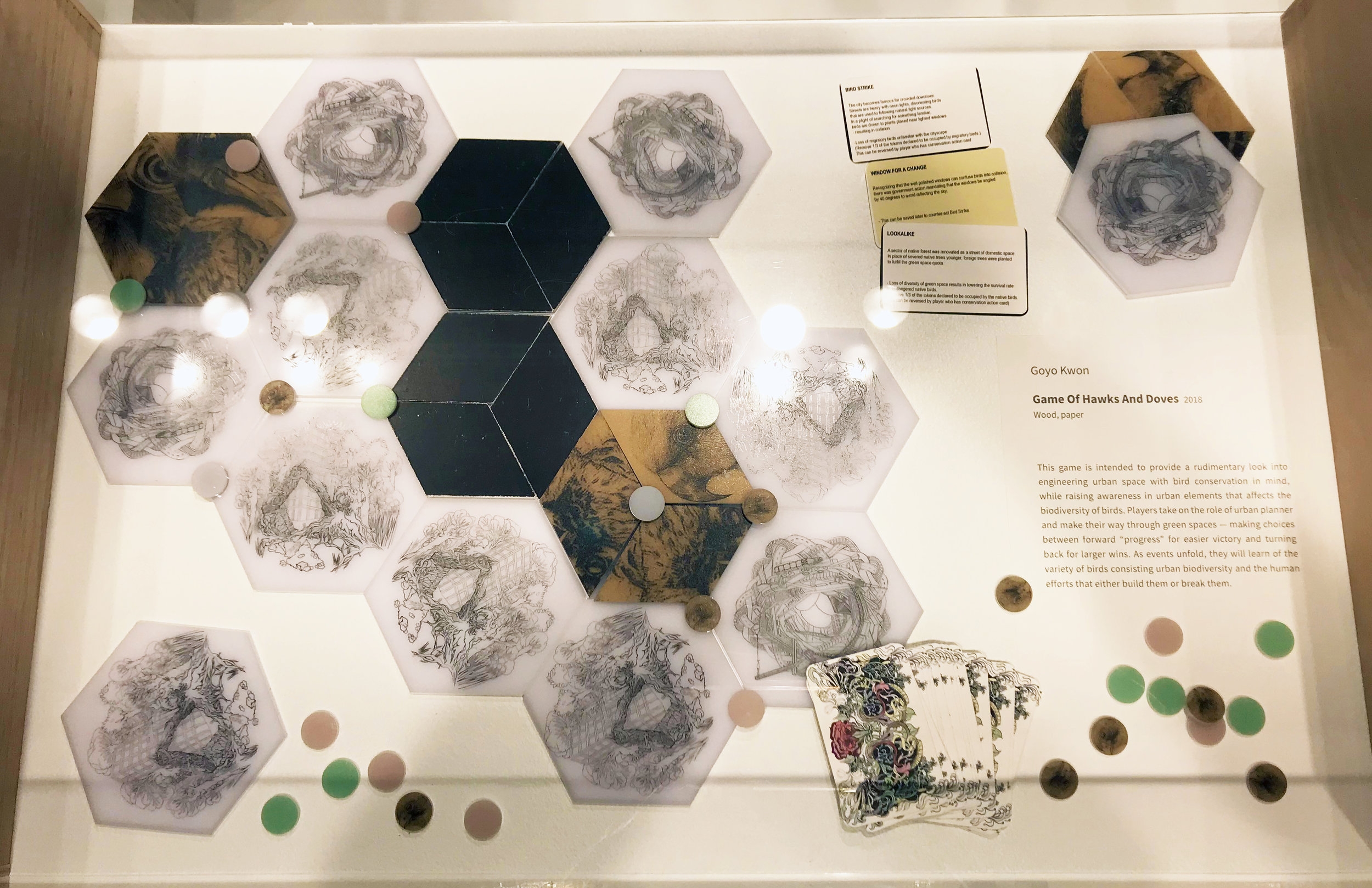

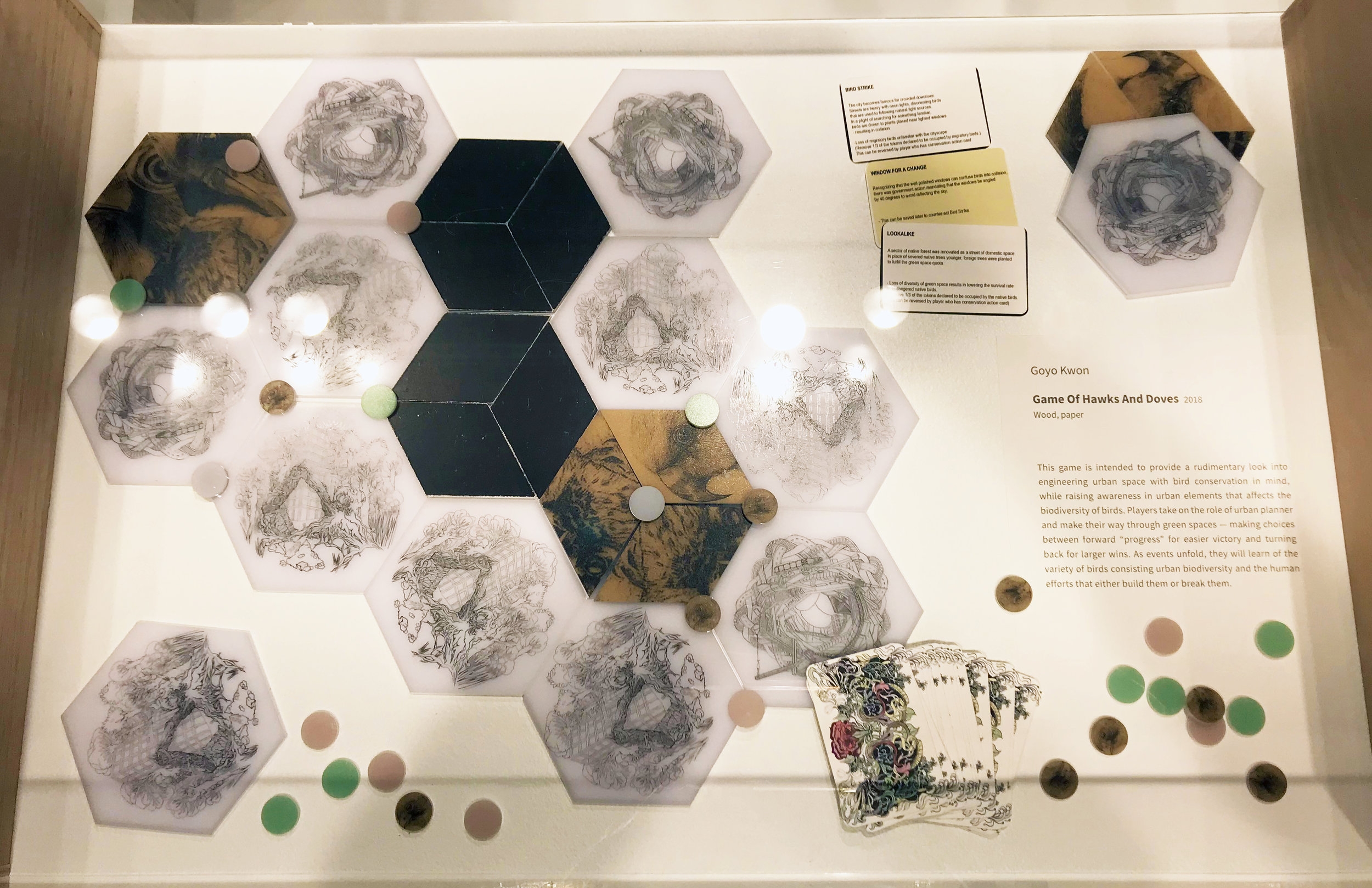

This game is intended to provide a rudimentary look into engineering urban space with bird conservation in mind, while raising awareness in urban elements that affects the biodiversity of birds. Players take on the role of urban planner and make their way through green spaces- making choices between forward “progress” for easier victory and turning back for larger wins. As events unfold, they will learn of the variety of birds consisting urban biodiversity and the human efforts that either build them or break them.

It was designed by a team of high schoolers including Hwa Yeong Jeong, a student of North London Collegiate School, Jeju. Her dream is to become a concept designer; she hopes one day her art will be displayed in films and games across the world.

My recent mixed media work occurs to me as a “hyperbolic flock of kerfuffles. I don’t mean to be flip. The onomatopoetic sounds of titles is a playful way for me to mix nature, science and art. The crocheted material in this piece is crisp, cool videotape. The armatures on which the textile is stretched and hung are scraps found on walks in the urban landscape. The method of knotting is feminine and familiar. The metal is rusty, but strong; likely something obsolete or tossed away as useless even. These “insignificat items are to be made precious by making them thoughtfully made and beautiful.

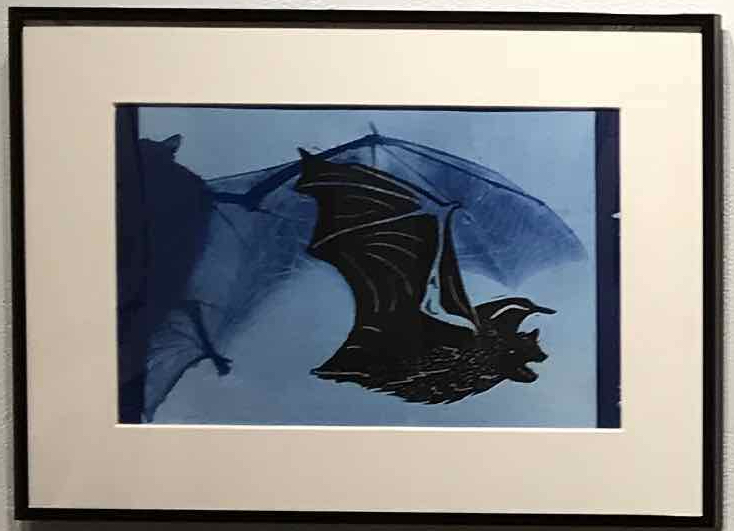

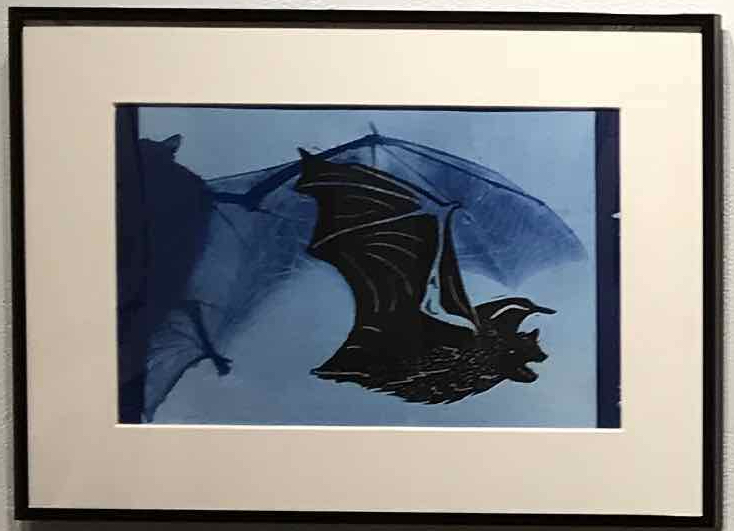

This sculpture was made to raise awareness of the only flying mammal, the bat, as it exists in areas of urbanization. The work is titled synurbic- meaning more frequent, or abundant, in urban areas than in other habitats, and Chiroptera- the taxonomic order of bats. As of 2011 there were 1232 documented species of bats. Many key words are selected from the article “Sensitivity of Bats to Urbanization: an overview” (Rossi & Ancilotto, 2014) are included in the sculpture. These small and sensitive species play a huge role in understanding ecological change. Hovering and creepy, excellent insect pest control, some bat species will thrive in urban areas, some will perish. Ultimately it is crucial to study and understand the variety of bat species within the visible and invisible realms of increased urbanization. What affects these delicate mammals will also affect us.

"Searching for Life" is an ongoing series of paintings of motion-activated camera trap photographs of animals.

On the backside of a hill in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, MA, I set up my camera to study the diverse native New England species that share a series of three underground burrows. Shockingly coyote, fox, fisher cat, raccoon, chipmunk, squirrel, and songbirds frequent these holes. Less than 100’ away lie the graves of famous naturalists and writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

With the photographs as reference material I have created a series of paintings that explore time (the changing of the landscape from day to night and seasonally), displacement (how many species 'share' this small abode), visibility/invisibility (an intimate, voyeuristic view into the animal's hidden lives) and rhythms (each animal's unique patterns of movement, use of the hole and daily/nightly habits).

Using the language of paint I fold beauty and darkness into visually complex and contemplative spaces where things may not be quite as they seem. I offer a playful, earnest and personal reflection of our interconnectedness of homo sapiens to fellow green, furry and living beings on this fragile blue planet.

"Searching for Life" is an ongoing series of paintings of motion-activated camera trap photographs of animals.

On the backside of a hill in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, MA, I set up my camera to study the diverse native New England species that share a series of three underground burrows. Shockingly coyote, fox, fisher cat, raccoon, chipmunk, squirrel, and songbirds frequent these holes. Less than 100’ away lie the graves of famous naturalists and writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.

With the photographs as reference material I have created a series of paintings that explore time (the changing of the landscape from day to night and seasonally), displacement (how many species 'share' this small abode), visibility/invisibility (an intimate, voyeuristic view into the animal's hidden lives) and rhythms (each animal's unique patterns of movement, use of the hole and daily/nightly habits).

Using the language of paint I fold beauty and darkness into visually complex and contemplative spaces where things may not be quite as they seem. I offer a playful, earnest and personal reflection of our interconnectedness of homo sapiens to fellow green, furry and living beings on this fragile blue planet.

Two Oppossum Tray: In the spring of 2015 a wildlife rehabilitation specialist approached me at a show to ask if I would consider a commission painting a baby opossum on a cup. “If people knew how adorable they are as babies, she said, maybe they would like them more as adults. Seeing a baby opossum first hand, I can tell you this is true; they are as adorable as kittens and puppies. We had a discussion that day about the benefits of opossums, how clean they are, with an appetite for ticks.

I took the commission and have painted opossums ever since. Having opossums on my pots allows me to engage in conversations about their benefits to the general public. It has given me a deep respect for these creatures. I enjoy the idea of them along with other animals inhabiting people’s homes as pottery. To join them at meal time and be companions around food and drink. It is a great was to bring the outdoors into the home. For the past fifteen years I have been exploring painting on pots and using an ash based glaze over an oxide wash and mason stain wash. I have chosen to work with this limited palate. Basically four materials, two ash glazes and two washes. I have made many discoveries about these materials over time, and continue to examine fired pots to uncover and investigate the complexities of how application of wash and glaze change in the firing.

Raccoon Moon: Wildlife biologist John Hadidian says, “How well do you know your neighbors? If you live in an urban area of North America, you might have a furry neighbor that you haven't yet seen." Raccoons have adapted so well to city life, they are now more common in cities than in the country.”The first time I really saw a live and wild raccoon was on an island in the middle of lake George in NY. I was a young teenager and my Dad, brother, and I were camping for a week on this small island. The camp campground was complete with picnic tables, a grill, and a metal garbage can. My dad woke me in the middle of the night to watch this bandit raid the trash. This seems like the quintessential raccoon story, in the woods camping in the raccoon’s habitat. What I have learned since that time is that there are more raccoons in urban environments than the “wild.” Everyone should have a raccoon story.

WELCOME TO THE ANTHROPOCENE. From melting polar ice caps and global climate change, to world-wide chemical residues of plastics and nuclear fall-out, to massive losses of natural habitats and ongoing animal extinctions, we humans have made our indelible mark on Planet Earth. These changes to the biosphere are so vast and unprecedented that many scientists call the current geological time-period the Anthropocene Epoch, “The Time of Humans.” My previous career as a wildlife veterinarian in Africa serves as the primary inspiration for my artwork. As a veterinarian, I actively and passionately worked on the conservation of endangered species, which included darting rhinos, moving lions, and capturing rogue elephants. As a response to these experiences in the field, my art portrays the collision between wild animals and human ecosystems. Crows are one of Nature’s adapters, able to co-exist with humans in altered environments, even cities, as long as their needs for shelter (trees) and food (including human garbage) are met. Yet, these intelligent, problem-solving birds can only manage by modifying their behavior to conform to human induced constraints. Internment captures this idea of animals contorting their behavior to fit within the confines we create for them.

Naturalist- nat.u.ral.ist- (noun) an expert or student of natural history

Both artists and scientists are “askers” of life’s important questions. My work spans the intersection of art and science through the investigation of specific species and ecosystems—I think of myself as a “cut paper naturalist.” In my artwork, I explore the ornithology, botany and ecology of ecosystems. I enjoy working with and learning from scientists. Each piece is individually hand cut using an X-acto knife and scissors, with up to several thousand tiny cuts per piece. The recipient of a 2015 North Carolina Arts & Science Council Artist Project Grant, I recently transformed 300 feet of paper into large-scale paper cuts featuring the 32 species of raptors being rehabilitated at the Carolina Raptor Center in Huntersville, NC.

Research from January - December 2015, included sketching and photographing resident birds, access to x-ray images from the Jim Arthur Raptor Medical Center, and the use of veterinary and ornithology textbooks. I completed preliminary research for my Raptor Project in the Bird Collection at the NC State Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, where I photographed and sketched in-articulated skeletons of various species of eagles, hawks, and owls.

"Blanketed" is an illustration created in hopes of spreading awareness of the vulnerable status and gradual urbanization of great blue herons and many other large wading birds in British Columbia.

Many factors affect the well-being of great blue herons, with deforestation and human encroachment onto nesting sites being major factors. I wanted to create an illustration that highlights these issues and encourages people to protect these beautiful creatures. Although the coloration of the illustration is somewhat somber and greyscale, I wish to convey hope and optimism through the splash of bright color across the image, and the comforting imagery of protection symbolized by the blanket.

This piece is a response to the urban coyote population and their struggle to coexist with humans. Light shining through the body projects the reasons the coyote are at odds with their surroundings. Special thanks to Numi Mitchell for her coyote expertise.

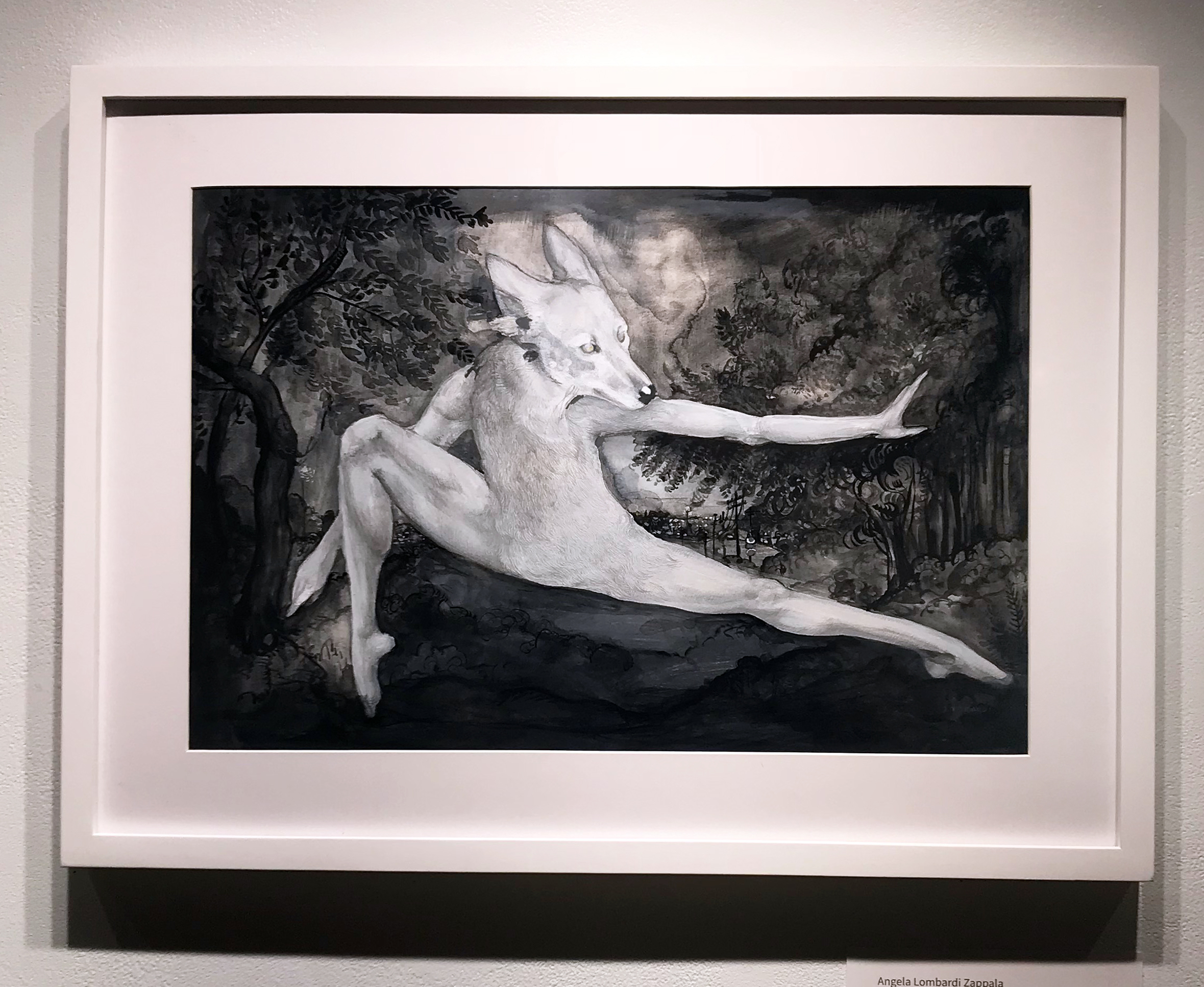

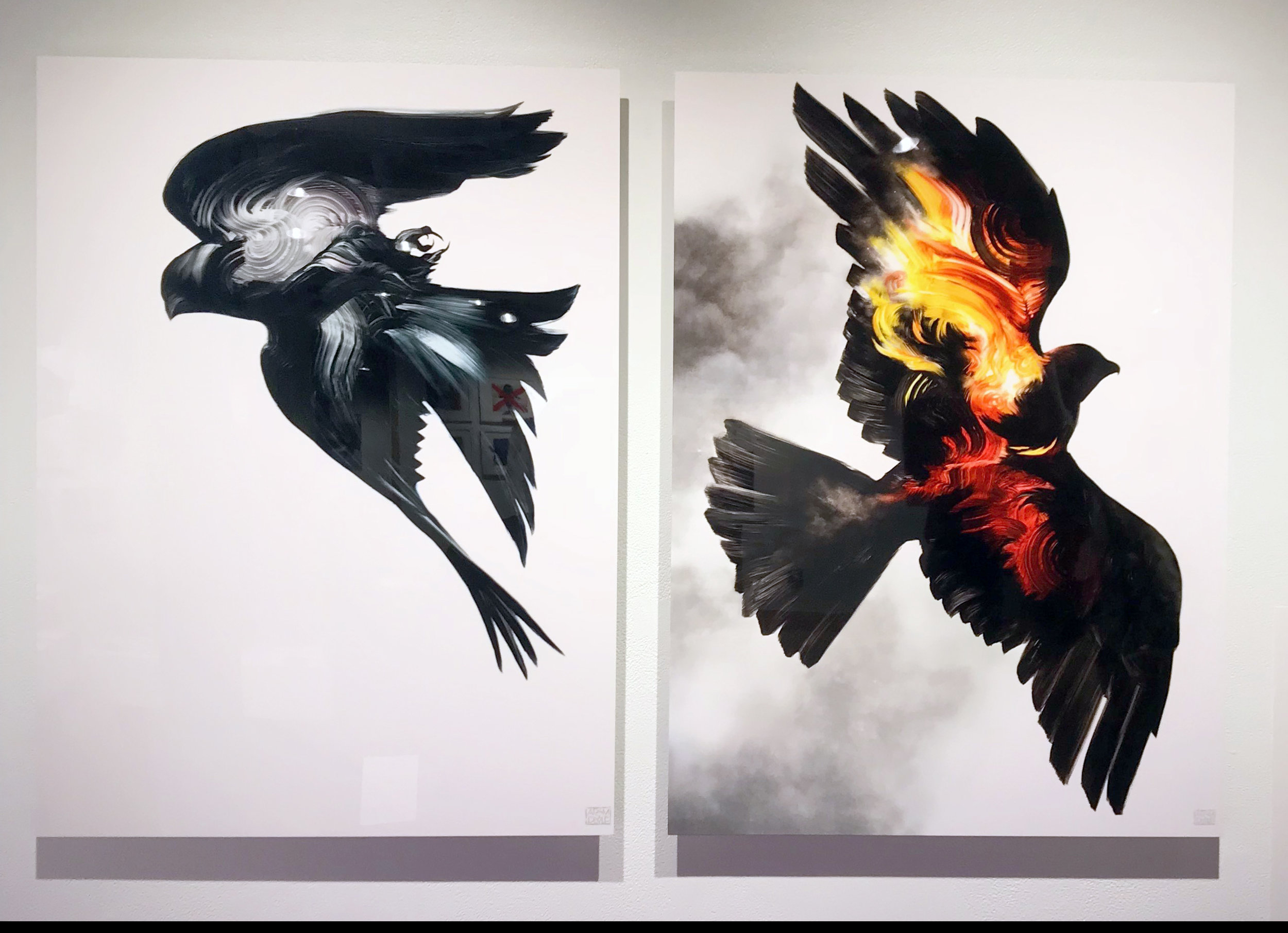

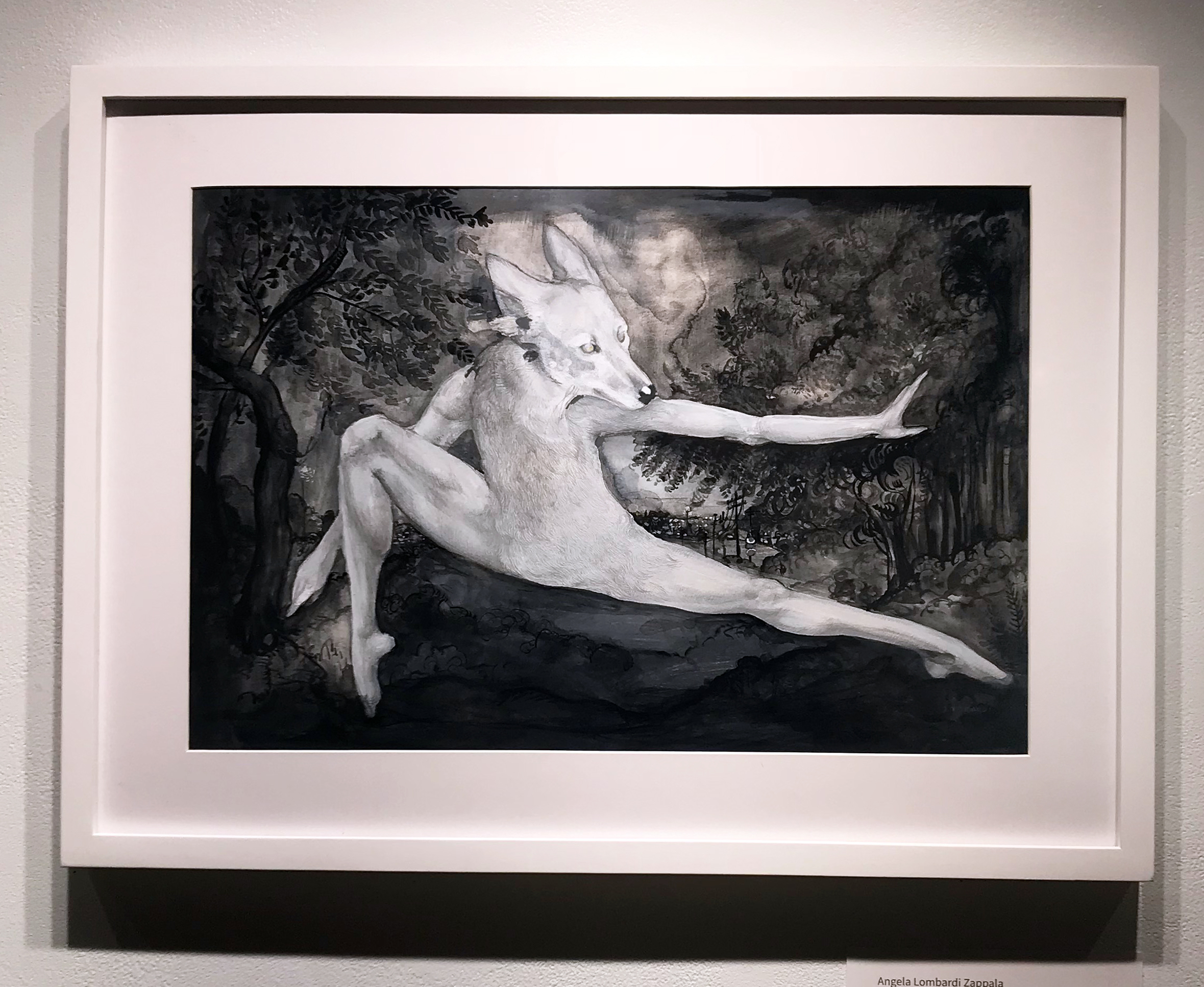

Many Americans have flocked to the suburbs with a white picket fence dream in their heads. But with our population on the rise and limited space, we carved our own area and expanded. We dug boulders out of the ground and uprooted trees in order to make foundations and fences. There is a certain hypocrisy and arrogance unique to humans in these situations, a notion that the world, and all it has, is under our ownership. Humans are continually developing rural areas and, in doing so, minimizing deer and other animals’ natural habitat. As a result, these creatures can be seen strolling through neatly manicured lawns and grazing on flowers blooming in gardens. Invaders, despite being there the entire time. Our reaction? Warning signs plastered on roads, warning drivers to take care lest a deer fly through their windshield out of nowhere. Hunters venturing out in camouflage and set up camp with the hope of returning with antlered trophies and venison, encouraged to “keep the population in check.” We celebrate our successes in taking up and taking over all of the space provided to us, but should anything dare to step foot in the areas we claim as our own they are dubbed an inconvenience, a pest, even a danger. These pieces urge people to look carefully at this belief that we uphold, confront it, and change it.

Many Americans have flocked to the suburbs with a white picket fence dream in their heads. But with our population on the rise and limited space, we carved our own area and expanded. We dug boulders out of the ground and uprooted trees in order to make foundations and fences. There is a certain hypocrisy and arrogance unique to humans in these situations, a notion that the world, and all it has, is under our ownership. Humans are continually developing rural areas and, in doing so, minimizing deer and other animals’ natural habitat. As a result, these creatures can be seen strolling through neatly manicured lawns and grazing on flowers blooming in gardens. Invaders, despite being there the entire time. Our reaction? Warning signs plastered on roads, warning drivers to take care lest a deer fly through their windshield out of nowhere. Hunters venturing out in camouflage and set up camp with the hope of returning with antlered trophies and venison, encouraged to “keep the population in check.” We celebrate our successes in taking up and taking over all of the space provided to us, but should anything dare to step foot in the areas we claim as our own they are dubbed an inconvenience, a pest, even a danger. These pieces urge people to look carefully at this belief that we uphold, confront it, and change it.

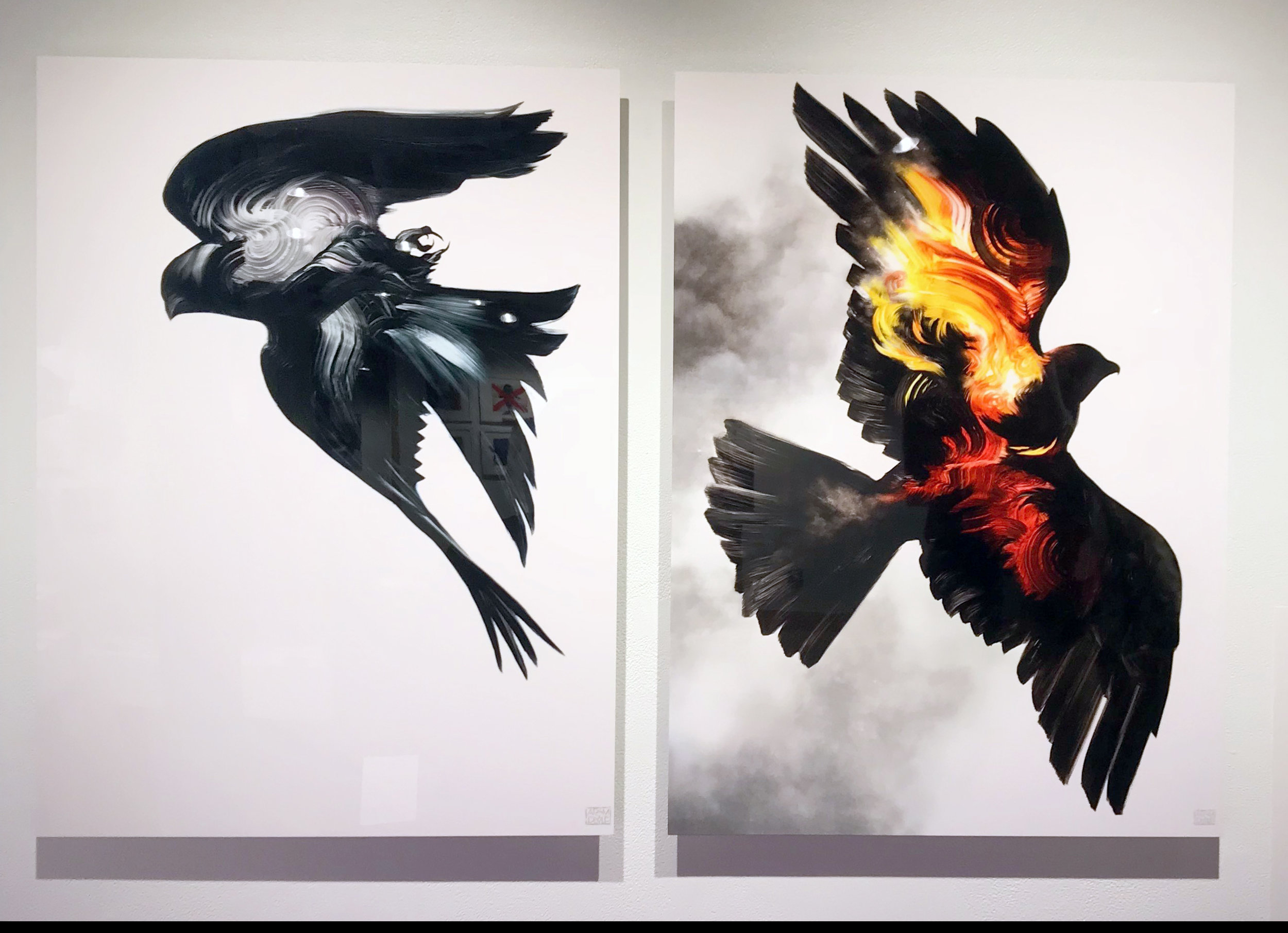

My work always begins with a love for the magic of creation- the blank surface transformed into a living thing or another world. This act has been with mankind since the first paintings on cave walls and yet never ceases to be awe-inspiring. I always want my marks to be visible, to keep this sense of wonder present. The story with my bird paintings took off when I was living in New York City and returned during my year in Hong Kong. Starting with the idea that birds, particularly the smaller breeds, are messengers of nature. Living in cities, surrounded by buildings and walking on concrete, nature can be forgotten as we commute to our jobs in metal cars and underground subway tunnels. Birds travel between both the natural and human-made worlds seamlessly. They remind us that animals aren't solely relegated to TV screens and zoos. Furthermore, historically they protect us with their song; in the primal recesses of our brains we know that when birds are silent, danger is near. When they sing, all is well in the neighborhood. There's also the symbolic quality they hold for us. Being able to fly, they embody our hopes and aspirations.

Biodiversity 360, is the result of a project started with the intention of rediscovering the city of my childhood. Over the years, rapid development and population growth has created a strain on the local environment of Guwahati, an erstwhile small North-Eastern Indian city. Guwahati, has been home to many species of birds and animals, some of which are endangered or almost extinct in the wild. For this project, I collaborated with Dr. Jayaditya Purkayastha, a local herpetologist and activist, advocating for cohabitation through his organization Help Earth.As a Maharam STEAM 2017 Fellow, I decided to closely work with Dr. Purkayastha, to build a simple engagement tool for students, residents and tourists, to discover an almost forgotten aspect of the city. The book cuts a rough cross section through the city, urging people to walk around and observe the urban biodiversity cohabiting Guwahati with us. It showcases key local species and suggests simple ways for humans to make the urban environment a safer place for co-existence.The book is accompanied with a small biodiversity map, which shares brief details of the species and the locality they can be spotted in.

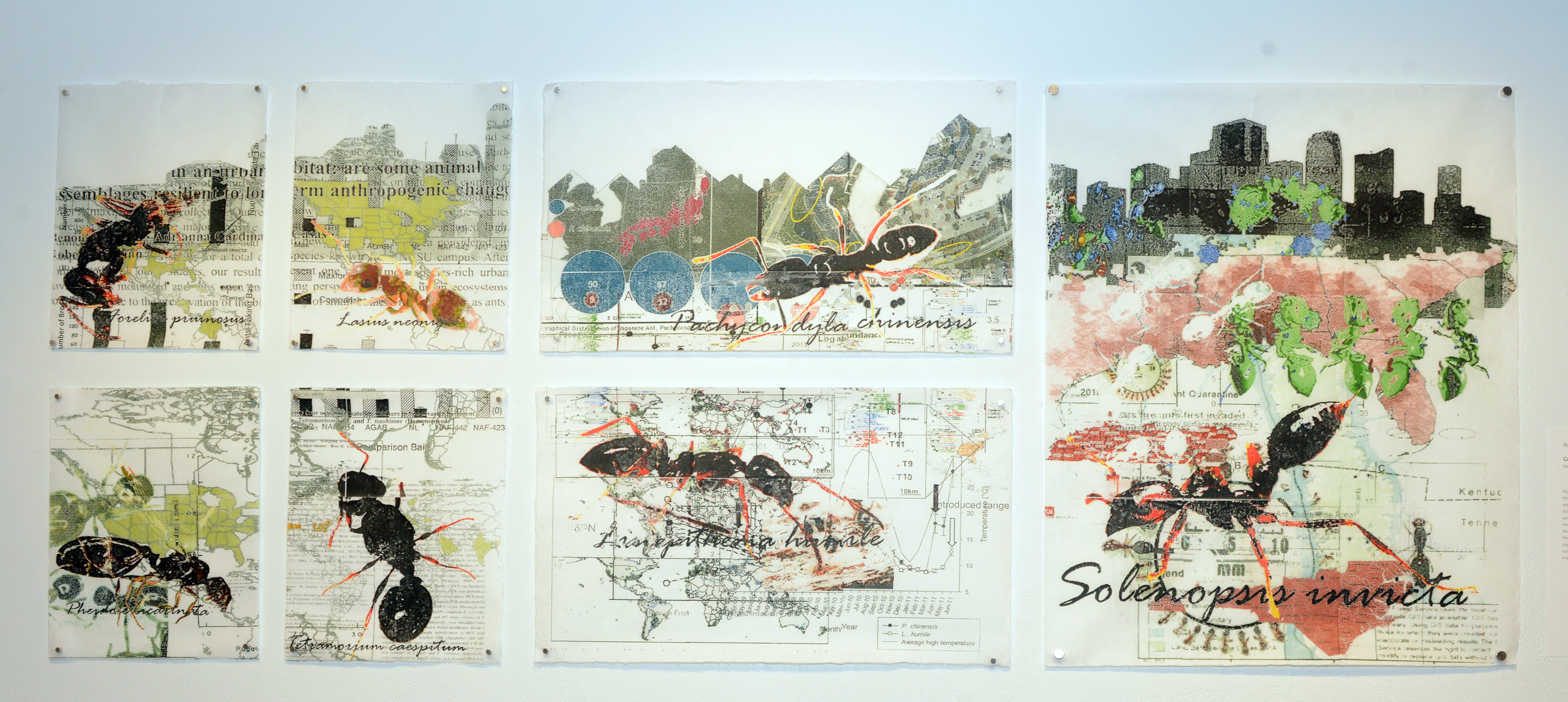

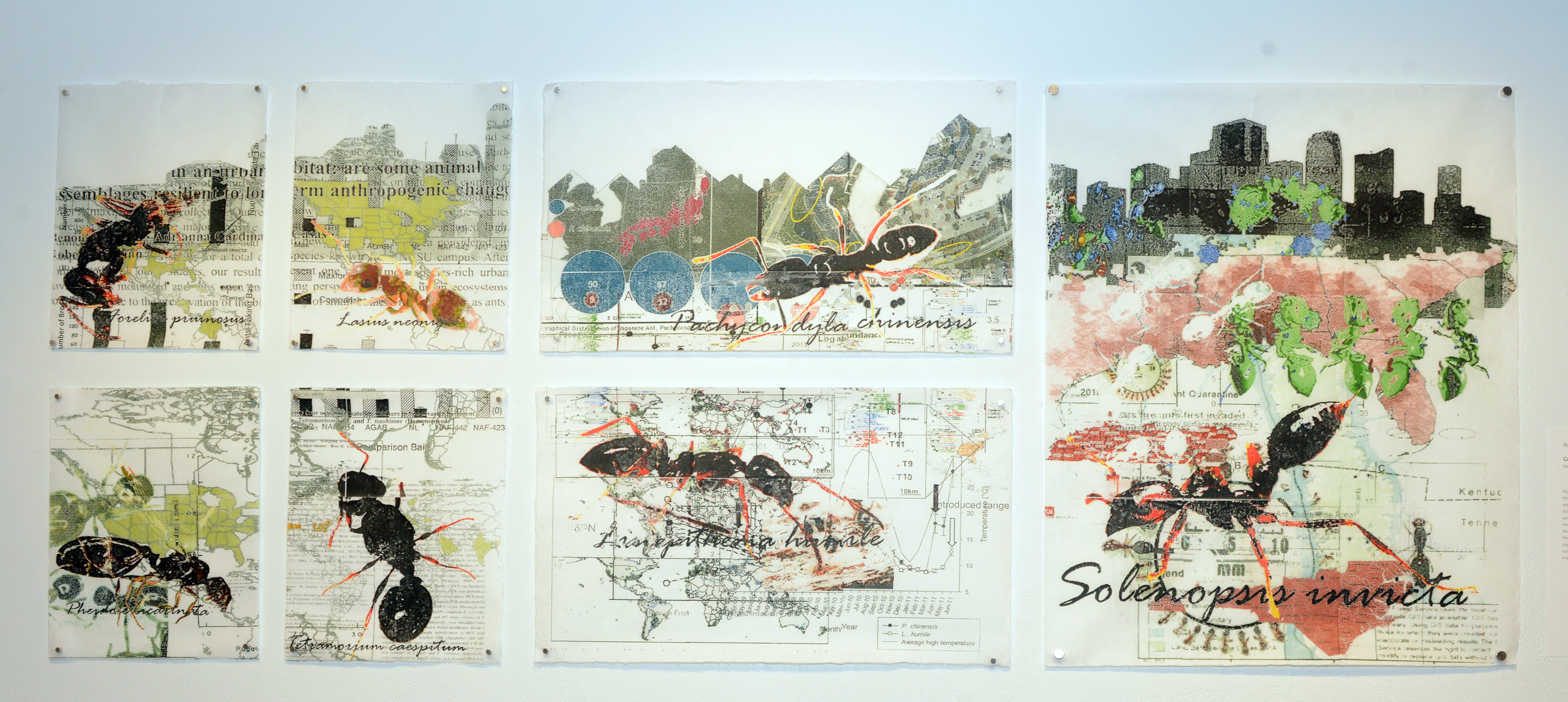

My work combines nature, science and art; three aspects of the impulse to explore and create. We believe humanity exists separated from nature, either as destroyers or protectors, but we are far from outsiders. In helping one species we hurt another, by preserving an ecosystem we slow evolution, by modifying one gene we alter them all. Ants make up 15-20% of the animal biomass of the entire planet, but human impact on the land allows some to thrive while others struggle. This piece explores the research being done into this process and the consequences of the massive alterations one species, humans, makes on the environment of another.

The Red Wolf, once a thriving predator in the Southeast of the United States, was placed on the endangered species list over 50 years ago and is now virtually extinct in the wild. Bred in captivity, there have been attempts to reintroduce the wolves into their natural habitat here in North Carolina, with very poor results. Habitation loss and hunting have left as few as an estimated 45-60 red wolves in the wild when surveyed in 2016. It has been determined that release into the wild should be halted until the human threat to the wolves has been addressed. My piece addresses the lures and the dangers that face the red wolf as it is released/reintroduced into its natural habitat. Humans bear the responsibility of destroying the population but are also the remaining hope for saving the species. Therefore the human figure is included prominently in the composition. The wolves can’t survive in the landscape decimated by humans, and they can’t survive without human intervention. Portraying this conflict was an interesting exercise in understanding what we do best, and where we fail. Research Source: "Managed movement increases meta-population viability of the endangered red wolf" https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21397 Juniper L. Simonis Rebecca B. Harrison Sarah T. Long David R. Rabon Jr. William T. Waddell Lisa J. Faust)

Due to climate change and its growing popularity as an ornamental landscape tree, the previously rare redbud trees have became fairly common and important for urban bee diversity in Toronto. Local wild bees, including Osmia lignaria (blue orchard bee, on right) and Xylocopa virginica (eastern carpenter bee, in the middle) are attracted to this early flowering tree. Leafcutters also use the leaves to build nest so I also included Megachile relativa at the top. Like the redbuds themselves, the eastern carpenter bee is at the northernmost end of its range, which is advancing northward with climate change, aided by urbanization (due to the urban heat island effect, which likely helps them survive our winters). In fact, since people are planting redbud trees in their gardens, we're inadvertently aiding migration of both tree and bee. What brings the X. virginica into conflict with its human neighbours is how female carpenter bees build nests by boring holes into untreated wood structures, including outdoor furniture and buildings. Thus these bees are often considered pests by homeowners and we are still working on 'learning to co-exist.' To emphasize this conflict, I printed weathered wood with round holes like those bored by eastern carpenter bees.

While the Northern Flicker is not an endangered species, it’s habitat in the urban environment is in decline. As we use more and more land for suburban homes, big box stores and parking lots, we have less land for trees. Wooded areas are now scarce. Because these birds raise their offspring in dead or decaying old trees, or “snags,” their future is in jeopardy. They compete with us for a place to live. We also poison their food. Unlike most woodpeckers, Flickers do most of their feeding on the ground. In the summertime feed on ants - an animal we try to keep out of our yards with toxic chemical remedies. There are solutions. It is important to retain uncultivated wooded areas, even small vacant lots in the city, where the natural world can have its way. These “islands” of wilderness are crucial to maintaining species diversity in the complex web of life. I agree with biologist and nature writer Bernd Heinrich who wrote that the best way to “manage” a forest is to leave it alone. Removing the messy stuff, the dying and decomposing wood removes an integral part of the healthy ecosystem. The benefits are not only for the animals. Frederick Law Olmsted understood the health benefits of retaining the green stuff of nature in our cities, too.

Bats have always fascinated and scared me. They swoop and fly so silently, so purposefully, and while they are mammals like us, they seem alien. As I learned about bats, I came to admire their design and appetite. Not only do they eat more than 1,000 insects a night (so there mosquitoes!), they have amazing bones. I corresponded with Dr. Lisa Cooper of Northeast Ohio Medical University, who is studying bat bone density and aging. Bats have evolved to disrupt the aging in their bodies and have exceptionally long lifespans for animals their size. Bats renew the collagen fibers within their bones as they age – their bones don’t become brittle like ours as they get older, but stay flexible. She said she held a bat bone in her hand and it bent easily. Dr. Cooper and her colleagues hope to study the fossil record of bat evolution to discover more about this renewal process. I thought about the bat as a marvel of engineering when making this image.

Highly intelligent and able to thrive in areas mostly populated by Humans, the Raccoon is one of the most popular mammals in our society. Although cute and cunning from afar, raccoons carry the sometimes deadly virus, rabies; humans themselves being harmful to raccoons. Yet the two need to and can coexist. Prowlers of the night, I wanted the strokes to be thick and bold and the colors to be contrasting to further display the difference in the two.

CURATORIAL STATEMENT

Human-wildlife conflict often results. Science can provide us with guidelines for how to live in balance with urban animals. For example, if we understand coyote behavior - they follow food sources - we can avoid problems. But we need the motivation to apply these solutions to our daily lives. There is an equally important need to help more people understand that humans and animals are interdependent and that our continued success depends on a diverse and healthy animal kingdom.

The term “urban wildlife” is a paradoxical one in many ways; exploring it may yield more questions than answers. For this exhibit, we define “urban wildlife” as any species of wild animal that is native or introduced, living freely in close proximity to people (villages, towns, cities) anywhere in the world. A partial list of urban wildlife species in North America includes bats, bees, coyotes, deer, elk, foxes, moose, *pigeons, peregrine falcons, raccoons, and red-tailed hawks. In other parts of the world, the choices for what is “urban” will differ. Elephants and macaque monkeys are considered urban in many parts of Asia, for example.

*We include pigeons because most are descendants of the wild rock dove, domesticated 10,000 years ago and still found in the wild, though in far fewer numbers than their city counterparts; rock doves are native to the rocky cliffs of Europe and Asia. We exclude feral domesticated animals for which there is no wild counterpart, such as cats, dogs, and typical farm animals (chickens, cows, ducks, goats, etc.)

ART/SCIENCE PROCESS

The artwork selected for this exhibition reflects the artist’s effort to explore, through a combination of independent research and collaboration with scientific experts, the basic biology of their selected animal or animals, its urban ecology, and the many ways it interacts with humans. Artists were given access to scientific references selected for this exhibit as well as scientific advisors to facilitate collaboration.

THEMES

Consider the following themes:

Time—how the urban environment changes as species leave an area, or return to it and reconstruct their environments

Space—how to define an urban ecosystem that can be as tiny as a puddle or as large as Los Angeles

Displacement—how people and urban wild animals displace each other depending on the circumstance

Visibility/Invisibility—how many urban animals are rarely seen or heard and how those we do see are moving or feeding

Rhythms—when and where urban animals breed, give birth, sleep, or die in the city

Health—how pollution (noise, light, soil, water, air) negatively affects humans and wild animals living in urban areas.